What impact will the pandemic have on the future of our cities? Only the history books will be able to say for sure.

However, our job as citymakers is to ensure that cities are fit for the many different futures that they might meet. The impact of the pandemic has created an opportunity to study how people’s lives are impacted when they are forced to rely on their immediate community for many of their day-to-day needs, from entertainment to access to green space. We wanted to investigate how lockdowns and the pandemic, restricting people’s movements to their neighbourhoods, highlighted the benefits and shortcomings of those neighbourhoods and the possible consequences for future design.

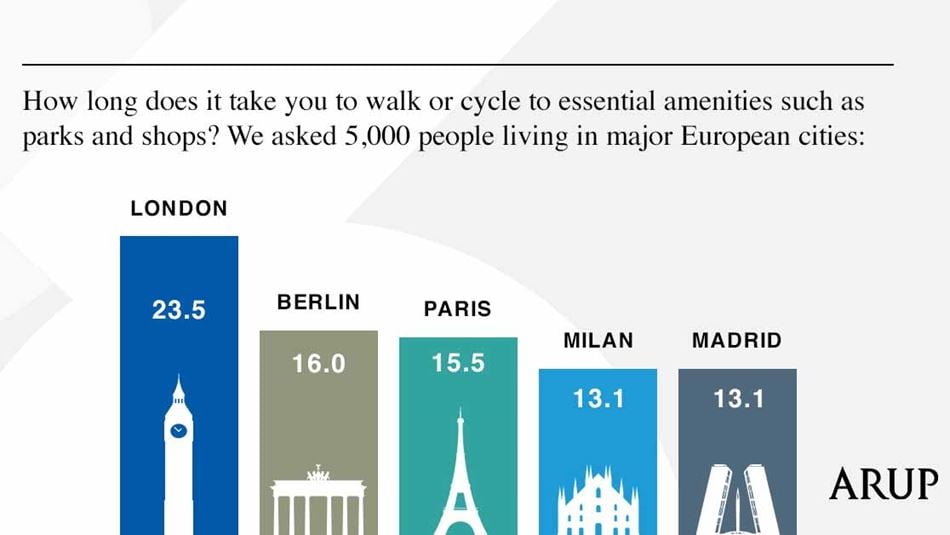

That’s why we’ve commissioned Arup’s City Living Barometer – a survey of 5,000 residents across five major European cities: London, Paris, Madrid, Berlin and Milan. The survey used the 15-minute city concept – which argues that people enjoy a better quality of life when amenities are within 15 minutes walking or cycling distance from their home – to roughly assess the liveability of each city. The idea was originally developed by Professor Carlos Moreno at the Sorbonne and espouses a new approach to urban design.

“We wanted to investigate how lockdowns and the pandemic, restricting people’s movements to their neighbourhoods, highlighted the benefits and shortcomings of those neighbourhoods and the possible consequences for future design. ”

Malcolm Smith Arup Fellow | Cities – Australasia Leader

What our survey found

Residents of London, Paris, Madrid, Berlin and Milan were asked how far they had to travel to green space, a shop that sells groceries, a medical facility, a school, a restaurant or café, and a leisure centre or gym. To gauge people’s attitudes to city life during the pandemic we also asked if they had considered leaving their city because of the pandemic or if they moved out temporarily at any point.

We found that London stood out compared to the other European cities as, on average, a 23.5-minute city. It also had by far the largest number of people (59%) who considered leaving and the highest (41%) that moved out temporarily (see table for comparison with other cities). Almost half of Londoners complained that amenities were too far away.

What this means for cities

For me, the results emphasised the importance of developing cities in smaller modules, with essential services around community hubs. A move towards the 15-minute city will help us hold on to the things we’ve gained temporarily – less traffic, cleaner air and, for many, more time with family.

Here are my thoughts on how to move towards a 15-minute city:

1. Focusing on walkability

Making the city more walkable by measures such as pedestrianizing shopping streets, planting more trees to provide shade and providing more benches and public toilets. Walking has been shown to make people happier and reduce air pollution. And a walkable neighbourhood increases the informal interactions between people, building ties among neighbours.

Find out more in Arup’s Cities Alive: Towards Walking World Report

3. Creating public space for play

We should be looking to maximise the opportunity for play. It’s been shown that child-friendly cities are friendlier places for everyone. Playful encounters can be built into everyday journeys through interventions that give objects purpose beyond their primary function and foster curiosity. Examples include playful bus stops, public art projects or pocket parks such as the Urban95.

Find out more: Arup Cities Alive: Designing for Urban Childhoods

4. Multifunctional space

In densely packed cities like London we need to look to re-use existing or outdated infrastructure such as car parks, school grounds or community hubs for neighbourhood activities after hours. Or looking to temporarily facilities, such as Kings Cross Central in London set up during its redevelopment – including an open-air swimming pool.

Find out more: Meanwhile use, long-term benefit.

.jpg?h=534&mw=950&w=950&hash=EC80FDBE6C7B646726F6A09E4B4AB5A4)

5. Creating digital twins

The ability to build online cities in parallel with our physical cities is within our reach. It allows us to model and test ideas that could ensure all developments help contribute to making urban life more enjoyable for communities by helping with everything from reducing air pollution to connecting people with green spaces. Digital twins allow the real-time simulation of cities – enabling policy makers and urban designers to test different scenarios and identify risks and opportunities. Crucially they will allow communities to understand fully the impact of different planning decisions.

Find out more: Digital Twins: Towards a Meaningful Framework

;

;