The COVID-19 pandemic gave Southeast Asian cities a glimpse into a more liveable future, as lockdowns cleared skies and brought a rare respite from gridlock and pollutants. Some cities went further, leveraging the lack of road traffic to experiment with car-lite concepts such as turning roads into bicycle lanes. Beyond enabling commuters to walk, cycle or travel using their personal mobility devices, I believe that active mobility is a necessary paradigm shift for cities in the post-pandemic era.

Here are three ways that I think Southeast Asian cities can get on track for a brighter post-pandemic future.

Do more with less – explore tactical urbanism

Cities can start small with tactical urbanism initiatives. This involves changing existing places and city systems through low-cost, temporary community projects to bring positive social and economic outcomes. The current low-traffic pandemic environment is the perfect time to do this, and change attitudes and behaviours towards active mobility. Although heat and humidity are oft-cited reasons in Southeast Asia for not walking more, I led a walkability study that found that Kuala Lumpur and Singapore have dramatically different levels of acceptance to walking. Interventions to pedestrian infrastructure and street design make all the difference in influencing perceptions of walking.

The Jakarta ‘Safe Routes’ project is a good example. Government agencies, public institutions and local residents collaborated on a temporary road intervention. They painted a pedestrian path on shared streets to improve safety and accessibility for pedestrians to get to school, home and a mass transit station. This low-cost pilot successfully changed behaviours – traffic was calmer and 98% of students who walked from their home used the painted path.

There are opportunities to pilot new initiatives and build on existing ones. Jakarta has begun remediating its interwoven canals, which can be turned into active mobility corridors that stitch together disparate neighbourhoods and forge valuable inter-community networks. Ho Chi Minh City could better leverage the transformation of the district in Thao Dien. In 2012 it turned a disused open area into a vibrant arts and entertainment venue, enhancing the precinct’s attractiveness and walkability.

Jakarta has begun remediating its interwoven canals, which can be turned into active mobility corridors that stitch together disparate neighbourhoods and forge valuable inter-community networks.

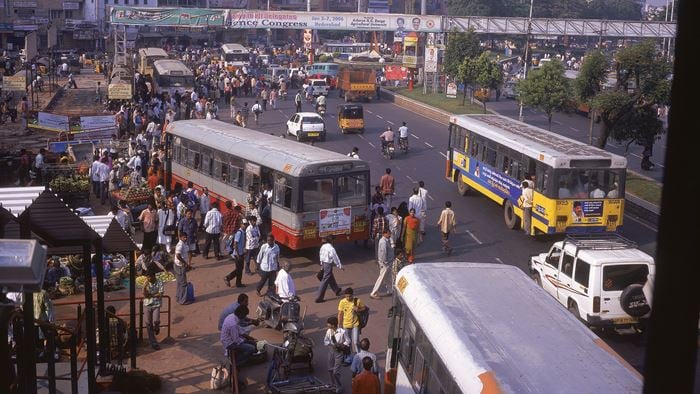

Make streets, not roads – invert the pyramid

City planners commonly plan roads before considering pedestrians’ and cyclists’ needs. While roads serve a purpose as corridors for movement, these wide swathes of tarmac often create severances within a city.

Streets, on the other hand, have a more diverse function. These are places where social and economic activity occur and deserve priority in urban planning. By prioritising streets, we are putting people and active mobility first, and cars second. We must invert the pyramid and make more streets, not roads.

By reconfiguring large sections of road space and car parking lots to be more ‘street-like’, London has demonstrated the tangible economic effects of elevating the status of pedestrians. Its investment in walking and cycling infrastructure increased retail spend by 30% and rental values by 7.5%. The economic benefits extend to higher property prices, rental yields and more employment opportunities.

Going beyond a people-first approach, Arup’s research has shown that a child-centric approach to urban planning can have highly positive outcomes. A child’s ability to get around independently and safely, play outdoors and connect with nature in an urban environment are considered strong indicators of high liveability standards. There’s better mental and physical wellbeing for citizens of all ages, too.

Create neighbourhoods as ‘campuses’

The pandemic compels rethinking of mono-use districts within a city. Due to lockdowns and work-from-home arrangements, businesses in areas such as Central Business Districts have been hit hard by the prolonged decline in human and economic activity.

Yet I have observed that 10-minute ‘campus-like’ neighbourhoods offering a diversity of amenities and experiences within a short walk or cycle from each other have been more resilient during the pandemic. Singapore’s Tanjong Pagar is an example of a successful 10-minute campus neighbourhood. Co-located within this vibrant and walkable district is a mix of hotels, retail and food options, public and private housing, heritage shophouses and skyscrapers – all stitched together by corridors of green spaces, interconnected footpaths and streets. There is something for everyone, and the diversity of visual and sensorial experiences make it attractive to stop, shop and walk – in turn, enhancing its resilience to the shock of the pandemic.

Active mobility is not just a transportation issue or a city planner’s problem. We’ve long known about the economic, social, public health and environmental resilience of precincts that prioritise active mobility. We just need to be better coordinators of different disciplines to transform our physical environment and engineer lasting economic, social and environmental change.

While big infrastructural responses work from the top down, we must also start small with tactical urbanism, transcend siloes with a collaborative and ground-up community approach to understand diverse needs, and refocus on people over cars.

Every crisis is an opportunity to outdo our previous successes. In this era of disruptions, let us focus not just on recovery and bouncing back, but on revolutionising and bouncing forward. Prioritising active mobility is a great place to start.

A version of this article first appeared in Urban Solutions, Adapting to a Disrupted World, Issue 18 by the Centre for Liveable Cities Singapore.

;

;