Upon first glance, the escalator and reinforced concrete have nothing in common at all. But when we dig a little deeper into how those products came to be, the similarity comes down to the people behind the ideas and the thinking which not only pushed boundaries in their approach to the design, but also in the approach to the broader applications.

Throughout history some of the most exciting design work has occurred at the intersection of two or more industries or disciplines.

The escalator was originally conceived as a Coney Island amusement ride. Reinforced concrete came about when a gardener was attempting to develop a stronger flowerpot. When the idea was ‘borrowed’ by the engineering and construction industry, it revolutionised the building process.

It’s this ‘borrowing’ of ideas, the cross pollination of skills, and a desire to push boundaries that are inherent in redefining what is possible.

Design, in particular engineering design, can be a very sequential process. It is a logical rational process of steps which take you through establishing a brief, generating options, testing and assessing these and finally providing a result – a design solution.

That process, although valid, provides little opportunity for inspiration, creativity and innovation. It can even impede designers from thinking more broadly or incorporate global trends and new technologies.

Breaking this sequential approach, which typically engineers and consultants can fall into, is only possible when we encourage and provide the freedom to explore the boundaries of ideas.

“To allow the design thinking to be broad, we need to play at the edges – explore and be receptive, work in areas that are new and push into those boundaries. We need to step into what some engineers would call a ‘chaotic’ zone – a space where exploration of ideas is not inhibited. We also need time to step away and let ideas incubate – allowing space for inspiration. Highly rational and objective processes are applied later in the assessment of these ideas. ”

Joseph Correnza Principal

It may be an oxymoron, but logic and ‘chaos’ can be a happy marriage.

By balancing the two, we break the sequential design process and allow creativity and innovation to seep in to the solutions we bring to each of our challenges and projects.

Engineers are trained to be logical, direct and objective. We aren’t trained in the art of open exploration, and the idea that it’s possible to work in both spheres is an idea that is uncomfortable with many.

But doing both is possible and some of the most exceptional engineers throughout history have done exactly that.

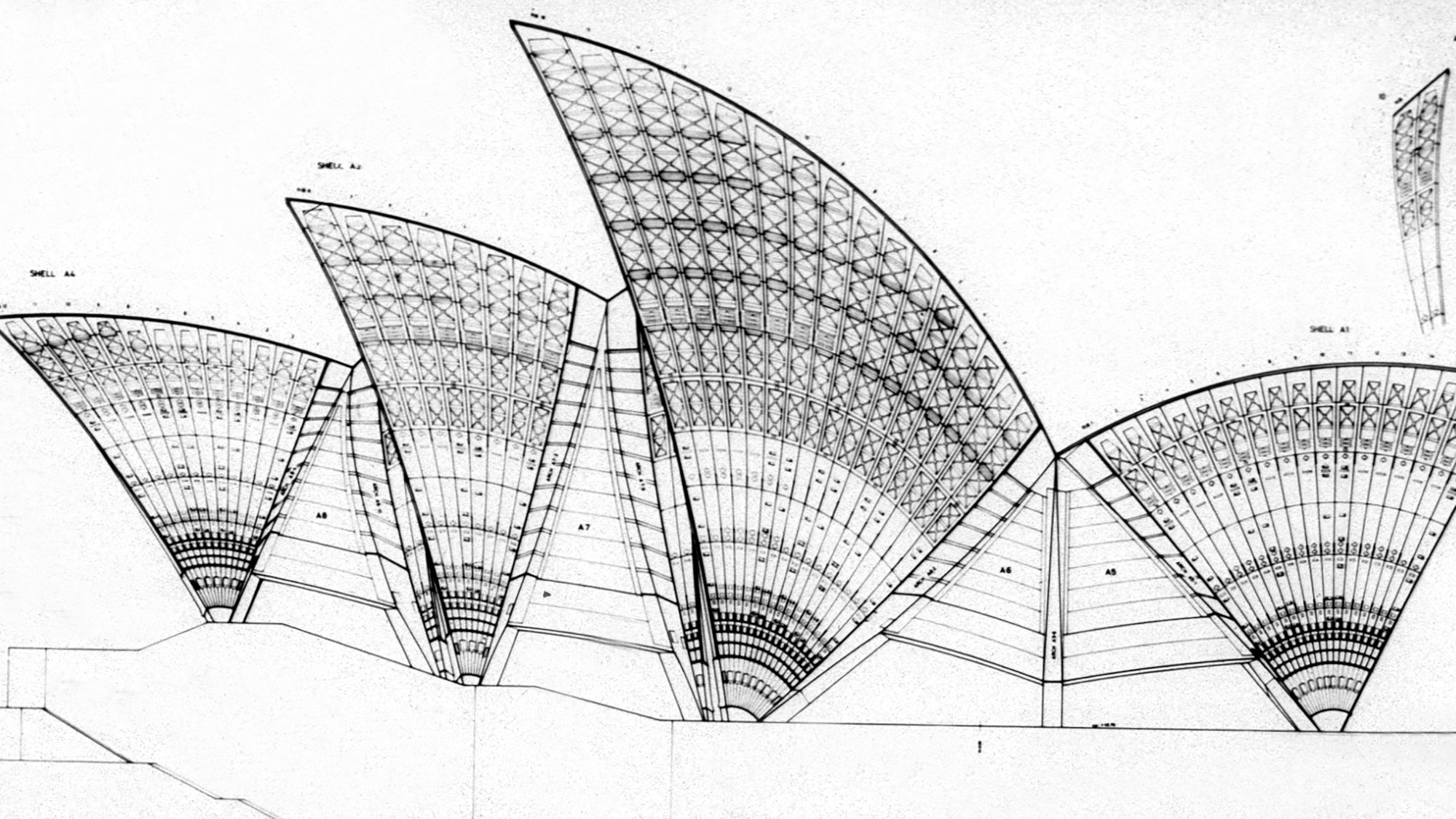

From the Sydney Opera House and the National Assembly for Wales, to the Guggenheim Museum Bilbao, China’s Watercube, High Speed Rail and Stonecutters Bridge, we have seen ‘jewels of ideas’ which have transformed the way problems are defined and solutions born.

The resolution of geometry around the Sydney Opera House shells was groundbreaking. Developing ideas that provided a solution to a highly complex form that was logical, rational, mathematically definable and hence buildable was a challenge overcome by an exploration of ideas generated from a state of immersion that tested the norm and entertained the ‘incredible’.

Some of our most ingenious ideas however don’t just come from iconic projects. Often it’s a less obvious detail within a project which when unlocked creates excitement and can have far reaching impact.

Ideas that generate elegant solutions such as fatigue resistant connections on the Melbourne Star Observation, or redefining the underpass and alignment of the Springvale Road and Rail Grade Separation, or resolving the complex springing geometry of the shell structures at AAMI Park.

Unique challenges cannot be solved innovatively by following predefined deemed-to-comply approaches.

They are resolved through clever innovative thinking around how to apply engineering principles to challenges, be it a buildability issue, or a macro geometric issue or the fabrication of a building component.

At the Bodegas Protos winery in Spain with Richard Stirk Harbour + Partners, changing our design approach led us to essentially fitting a ‘square peg into a round hole’, or in this case marrying two opposing forms of geometry – an efficient parabolic structure supporting a repetitive semi-circular barrel vault roof.

The problem of marrying the two types of geometry stumped designers for months, however by exploring ideas uninhibited and collaboratively we unlocked what seems now an obvious but very powerful simple idea – divorce the geometries by offsetting one from the other.

In hindsight, some of the best solutions seem simple and obvious. Elegance in design is usually uncomplicated, clear and not convoluted. Achieving apparent simplicity can however be the result of a hidden long process, pushing and testing ideas.

The value of unlocking any design challenge can be directly tangible and indirectly far-reaching. Reduction in costs and construction time are usually obvious, however wider ramifications on those who use the facilities, or how amenity is improved for the wider community can be less obvious but equally if not more important for the long term sustainable future of our cities.

Once you’ve unlocked a solution a new benchmark is created for doing things better in the future.

Good thinkers are found in all disciplines and industries. Learning from each other is fundamental in pushing design thinking. If you work in a uni-disciplinary mindset you don’t get that cross fertilisation of ideas that can occur between different parties, and that’s why encouraging a broad variety of disciplines to participate in design thinking is so important.

We see boundaries being pushed every day by different industries – from 3D printing of componentry to use of new material technologies. The aeronautical and automobile industries are using tools and technologies, which can also be applicable to the design and engineering construction industry. These include advanced virtual modelling and direct component manufacture, to optimisation using advanced computational fluid dynamics for air-flow modelling.

We are already sharing innovations across these industries and look to cleverly apply these to our design thinking.

On the Springvale Road and Rail Grade Separation project we saw how innovations in component manufacturing contributed to an overall construction programme reduction and consequently cost savings of tens of millions of dollars for the client.

Design thinking that incorporates collaboration, sharing and across disciplines and industries will improve how we design, integrate and experience our cities.

Across our industry we are in danger of our design process being degenerated as commoditisation of engineering becomes more prevalent. The outcome will be a process that encourages uninspired thinking with equally uninspiring outcomes.

Exploring at the boundaries of what is possible in terms of design, sustainability, innovation and technology is the smartest way to continue to improve and shape our projects which will ultimately challenge the spaces we occupy within the cities we experience, as a community and as individuals.

;

;