Mobility is in the midst of a major period of change — one that will drastically transform cities, just as the introduction of the automobile did in the last century.

When I first wrote that in August 2016, we practitioners were still coming to terms with the speed and scale of this change. New mobility is what I saw at the time as the convergence of mobile apps (fare payment and traveler information), automated vehicles, changing user expectations, and new business models that would change both transportation and cities.

Fast-forward and I wonder where we stand on the continuum of change and how we have reacted thus far. And, most importantly, what does it mean for the future?

*

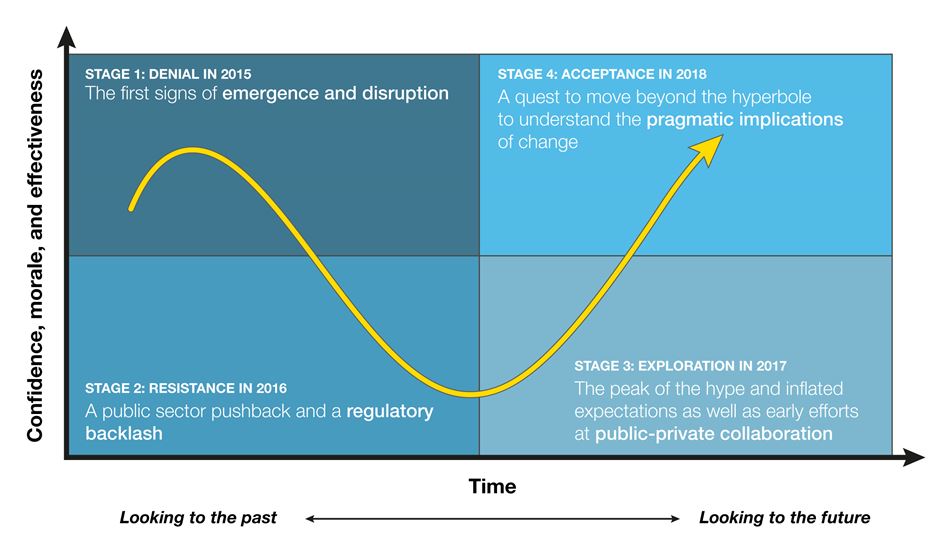

The first signs of this wave of emergence and disruption in the mobility sector surfaced in 2015 in larger urban areas where mobile apps, shared services, and early automation were taking hold. The private sector began pushing into processes and regulations previously dominated by local government operators. While technology and automation were seen by many as silver bullet solutions to urban problems, for government operators it was a period of discomfort and denial.

The next year, 2016, saw the beginnings of a public-sector pushback with a regulatory backlash that slowed the momentum of the disrupters. That year also marked the peak of the hype and inflated expectations around automated vehicles. By 2017 early efforts at public-private collaboration had begun to emerge, heralding the exploration phase of pilot programs and a greater sharing of information.

So where are we now? 2018 has been about acceptance, moving beyond the hyperbole and developing an understanding of the pragmatic implications of change. 2018 has also seen a renewed push by the private sector for scale and market share, prerequisites for successful commercialization and sustainable business models. As we move forward into this new period, there is plenty of work ahead.

Our clients and collaborators will have to navigate these turbulent waters, raising two key questions: when will changing mobility affect cities in a meaningful way and, with so much uncertainty, how do we make resilient plans?

When will it happen?

The short answer is that changes in mobility will happen much faster than most think, but more slowly than technology companies would like. Deployment of new technologies can be quick, but adoption requires user acceptance, government regulation, and sustainable business models, which together are no small hurdle.

When will changing mobility affect cities in a meaningful way and, with so much uncertainty, how do we make resilient plans?

Take, for example, the contrasting development fortunes of Car2GO and Uber in Toronto. Both are popular and proven brands with high customer acceptance, one in the car-share market and the other a ride service. Early on, Car2GO held a strong market position, including agreements with the City of Toronto on the use of parking lots, and a seemingly promising business model. Uber, in contrast, initially operated outside City regulations but invested heavily in growth. As that growth propelled them to new levels of popularity, Uber stepped up to the negotiating table to hammer out agreements with the City on operations and a limited sharing of data. Meanwhile, despite its early prominence, Car2GO came to an impasse with the City over the issue of free-floating cars being allowed to park on city streets. The company considered this one regulatory issue fundamental to its business model and, despite their solid technology grounding, has since withdrawn from Toronto.

Now that the first wave of over-hyped expectation is over, particularly for automated vehicles, it’s easy to slip back into complacency. Just because change is incremental, however, does not mean it will not be transformative. Consider the first North American highways, built in the 1950s. A lone highway in an otherwise sparse, rural landscape was certainly not only change but progress. But while futuristic visions surrounded the rollout of this first mega-road, the on-the-ground reality was much more incremental. It’s only in hindsight that we see the cumulative effect the introduction of the highway has had in fundamentally reshaping our communities.

Transformative change in mobility should be measured in decades rather than years.

How can we navigate uncertainty?

As planners and engineers, we have been trained to develop a preferred, or normative, future scenario, which our polices and infrastructure investment plans are then designed to work toward. Since the last few decades have been ones of relative stability, where extrapolation of past trends was a fair prediction of future conditions, this approach has been successful.

Now, basic assumptions are changing. If we are in a phase where change is the only real constant, then a single, pragmatic path forward does not exist. In this environment it’s easy to default to no action and this has been the case for many organizations over the last few years.

There is a need, therefore, to think about the future differently. Adopted future goals will remain useful tools, but the process of adopting them should be done with a strategic approach that considers how the plan of action can be resilient across a range of potential futures.

In foresight and scenario planning we consider a wide range of change drivers that affect all sectors of the economy and society. From these, we create plausible future scenarios to shape our thinking about today’s challenges.

Using scenario planning in a multi-stakeholder environment has two benefits. First, creating scenarios allows planners to step back from day-to-day operations and consider broader and less immediate factors that will shape a business or city going forward. Second, the process can foster necessary collaboration and dialogue to tackle increasingly complex urban challenges.

As an example, I worked on the planning and design for a new terminal and transit center at the Toronto Pearson International Airport. Future drivers of change can have a big impact on design parameters for these facilities, from the sizing of various airport functions to the relationships between the different functions. We had to consider potential disruptions, many of them outside the control of the airport authority, such as biometrics, off-site check-in, AVs, supersonic or electric aircraft, and changing airline alliances and industry practices. By thinking through the potential implications of multiple future changes we can help clients manage the risk of either over or under designing a facility in the face of uncertainty, while also adding a measure of flexibility to our future designs.

Conclusion

We are entering a new phase of change that, like it or not, will be characterized by even more change. In the mobility sector, we can expect a substantial shakeout, consolidation, and convergence in the industry as an unavoidable consequence of automation, the digital economy, and, hopefully, increasing efforts to harness technology for the public good.

The early signs of this shakeout and consolidation can already be seen in both government and the private sector. Technology companies, platform providers, car companies, and app developers have all focused on achieving scale and position in the market while simultaneously working to evolve a sustainable business model.

Uber, for example, is currently valued at $72bn, but has yet to turn a profit (its recent bump from its transactions in Russia and Southeast Asia notwithstanding). It’s still refining its service offering and business model and is grappling with the extent to which automation will play a factor in the company’s future. Uber is exploring bike share and also forming partnerships, such as the recent $500m investment by Toyota to advance self-driving vehicles. Similar investments are happening across the sector, such as the $17.5m investment by Alliance Ventures, the strategic venture capital arm of Renault-Nissan-Mitsubishi, in a multimodal transportation app (Transit App).

In the case of emerging mobility, the conversation has shifted more quickly than ever before from the benefits that technology brings and how to deploy it, to questioning our vision for cities and how technology can help achieve our objectives. And that is why this article is titled “The end of the beginning.” The changes initiated in the first disruptive phase have yet to fully manifest themselves in our daily lives. And, as with any seismic shift, we can expect a series of aftershocks and adjustments that can prove almost as challenging as the initial disruption. The challenge of truly harnessing the societal benefits of improved and increased mobility still lies ahead of us. This is, my friends, merely the end of the beginning.

;

;