Starchitects aside, we hear little about the individuals whose cumulative decisions shape the built environment. In our Profiles in Design series, we chat with engineers, architects, policymakers, and designers about their lives, careers, and daily aspirations.

Arup’s David Farnsworth, our property market leader, principal, and civil/structural engineer in our New York office, discusses his discipline-blurring career at Arup; the future of design in New York City and the architecture, engineering, and construction industry; and his go-to sources for innovation and inspiration.

Do you remember when you first became aware of engineering or when you first decided that was what you wanted to do?

Growing up, my dad was a home builder and concrete contractor. As early as the seventh grade, I was working over the summer, pouring concrete with my dad. I loved seeing this physical embodiment of what you’d accomplished at the end of a day’s work.

On the school side, I was always good at math, science, and physics. When I went to college, I started in chemical engineering — only to quickly realize I hated chemistry. Civil engineering, on the other hand, seemed more like what I had already been doing during the summer for eight years, and more of what I enjoyed. It felt like a way to stay involved in that type of work without being out there on my hands and knees, in the hot afternoon sun in Louisville, Kentucky, finishing concrete all day.

What key aspects have defined your 22-year career?

As part of my master’s degree, we took a trip out to California to visit seismically resilient buildings and the engineering offices that worked on them, which included Arup’s San Francisco office. Most of the firms we visited were single-discipline teams, but Arup had structural engineers sitting next to mechanical or plumbing engineers, and I thought, “How awesome would it be to work at a place where you could be exposed to all aspects of the built environment?” I know now that this concept of multidisciplinary, holistic engineering was referred to as “total design” by our founder Ove Arup, but this idea resonated from the very start. So when I graduated, I joined Arup in New York on the civil team as a bridge engineer.

I spent four years designing bridges. Then one of our structural engineers pulled me onto a project for a large-span convention center roof in Korea because it was very similar to a tied-arch bridge project I had just finished. That was my entry into building engineering. On that project, we started integrating our structural work with the skills and services from our Advanced Technology and Research group, using non-linear analyses and DYNA modeling to make all of the structural hollow sections for the roof connect together and efficiently transmit forces without needing ugly, heavy stiffening-plate connections. At the time, there were no code-prescribed methods to design tubular steel connections that would be applicable for the geometry we had on the project, so we tested them virtually. I love these challenging structural problems best because we can bring the brain trust of Arup together to come up with new ways to design and build structures.

The convention center client loved what we did, so my next project was a 300-meter tower right next door with the same client, starting a shift to designing tall buildings all over the world.

The Little Island project in New York City ©Michael Grimm Photography

Do you have a favorite project?

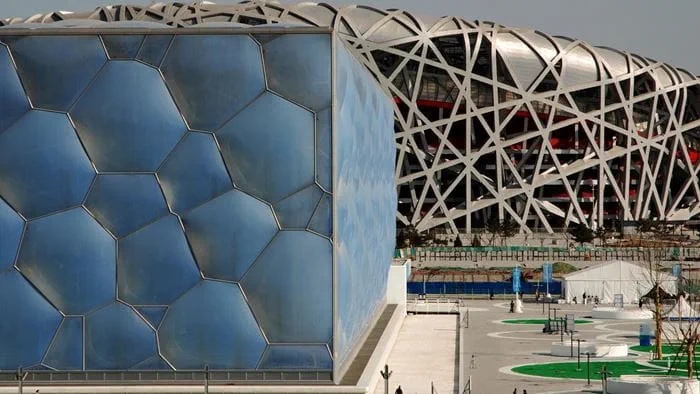

I've worked on some fantastic projects, from the tallest building in Beijing and Marina Bay Sands in Singapore to projects in highly seismic Mexico City.

Locally, the Little Island project in New York City, a public park on Pier 55, is readying to open — that’s definitely at the top of my list. First, it’s a great design by Heatherwick Studio from an architectural sense. You look at it and say, “Wow, what’s that?” The design itself is this eye-catching structural sculpture. As a result, we had a huge part to play in realizing the architectural vision. We pushed boundaries and used digital fabrication and parametric modeling to create precast concrete formwork that still has this organic, irregular look. It is tricky to subtly get repetition in the forms to ensure precast concrete as an economically viable solution.

Second, it was a hugely collaborative process among the architects, designers, client team, and construction manager. We found some amazing marine construction contractors and precast concrete suppliers to embark on this journey with us. They developed a new business division to robotically mill foam formwork, and we blurred the boundary between contractor and engineer by taking on shop-drawing-level 3-D modeling work, where we issued rebar models direct for fabrication. It was great to have everyone thinking outside the box of traditional scope boundaries to deliver something exceptional.

What’s happening in design right now that’s most exciting to you?

There are a couple trends that have me excited about the future, particularly prefabrication, digital fabrication, and the ways in which we transmit information to our collaborators. We used to hand-draw our designs, then computer-aided drafting revolutionized the production of our design deliverables, opening up new possibilities for building geometry typologies — basically enabling totally new building forms.

Now we’re at another inflection point with parametric design. We're starting to effectively write computer scripts and algorithms to iterate on designs and deal with increasingly complex geometries. We’re also able to create models that convey information in 3-D, so that, as we did on Little Island, we can directly issue models to a manufacturer who then sends our models to a robot to mill foam formwork to create these complex 3-D shapes.

3-D rebar model for the Little Island project

I think being more involved in these processes, rather than trying to shed risk by staying out of any construction means and methods, is hugely critical to the future of our industry. We can find great value by examining the ways in which our design information is realized. And, if we’re able to automate the production of more and more of our work, we have more bandwidth to explore.

What kinds of changes or adaptations are you seeing related to pandemic and climate change stressors?

For a variety of reasons, there will be a renewed focus on assessing existing assets. I don’t believe that COVID will be the death of the city center, but I do think the tie between our economic growth and building new office and residential properties in dense urban areas will weaken.

We know the need for central business district office space is going to diminish. People have realized they can be equally or more productive from home. At the same time, the connections we make in the office and the intel that we gain by being close to one another are still needed. I think there will be a significant reassessment of the optimal shape for office space. If less office space is needed, there are opportunities to convert existing assets to new uses. From a sustainability standpoint, that's the best thing we can do — reuse existing hard assets rather than creating new concrete, new steel, and adding carbon to the atmosphere. The conception is that new construction is cheaper than remodeling, but rehabilitated historical structures have a character that’s hard to put a number on and extremely appealing to occupants.

We’re also going to see interesting innovations in terms of building controls. The monitoring of our building spaces for health and well-being metrics is going to be increasingly important to occupant comfort. COVID and the potential of other pandemics will be with us for a long time. Clear and transparent communication on the safety, air quality, and occupancy of our buildings and infrastructure will be in huge demand.

Zuccotti Park in downtown New York

As a New Yorker, how do you see the city shifting post-pandemic?

Over the years, there have been several stressors that have driven significant change. Going back 50 years, you could start with the conversion of old warehouse buildings into lofts and residential spaces. In the years following the 9/11 disaster, while downtown Manhattan was effectively cut off from the rest of New York, several office buildings converted to residential, which completely changed the dynamic of the area.

Similarly, after Superstorm Sandy flooded lower Manhattan, many office buildings, especially those with electrical infrastructure in the basement, were flooded and shut down. Many canceled their leases and renovated to residential. Each stressor has eventually further activated the neighborhood at night and given restaurants a better chance at viability.

Each of these changes has made the neighborhood better after a period of distress. I expect the same to happen as a result of COVID. Maybe there will be a better distribution of livable communities within New York, or maybe there will be a better balance between commercial and residential uses that give each of the neighborhoods a more active vibe.

Where do you draw inspiration from?

First, I do my best work when an architect or owner wants to do something fantastic and different, but also wants it to be economically viable. In those moments, it pushes me to do something that isn’t square, while giving practical advice to make these ambitious architectural visions work. An engineer at heart, I often find that the simple solution is the most elegant.

Second, inspiration often builds on innovation. Whether it’s designing convention center connections using advanced finite element analyses to model non-linear behavior or innovating the Little Island construction process with robotics to minimize manual error and allow structural pieces to come together seamlessly, these are the drivers that get me excited about work.

And finally, we’ve got some really smart people at Arup. It’s always fun to have a concept design review where everyone throws out ideas and see which catch. Whether in the office, at home, or working on projects with collaborators overseas, it’s continuously inspiring to work with amazing people.

;

;