In 2019 the Australian chief scientist, Alan Finkel, gave a speech to an international audience of government scientists in Washington, DC. He explained how using electricity generated from solar power to produce hydrogen will give Australia, and other countries, an opportunity to “ship sunshine at scale”, and help the world drastically reduce carbon emissions.

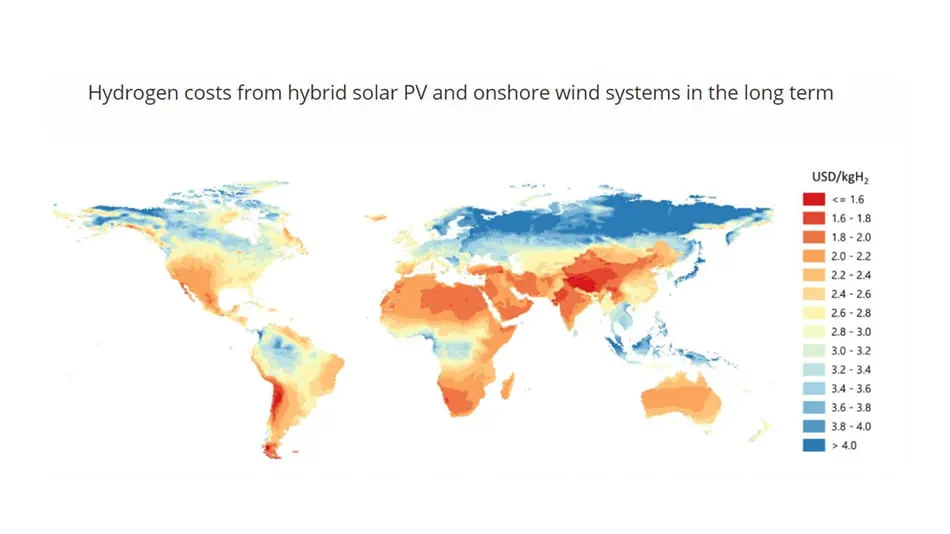

Scientifically, he is correct. Looked at on a map of the world, renewable energy presents a puzzle: abundant and cheap in many areas, it is notably absent in others where energy consumption is high. Green hydrogen, hydrogen produced from renewable electricity via electrolysis, presents the opportunity to be transported with less energy loss than electricity around the world.

From a markets perspective, however, there are plenty of other moving parts, from state-level politics, rivalries and balance of trade concerns, to the rights of populations who may have to make way for giant solar farms. Between this there will be corporations, working out how they fit into an energy revolution and, of course, a significant amount of investment. How this will play out is not fully clear yet, but there are some ideas we can place around it.

Scale and emptiness

In his 2019 speech Dr Finkel estimated that 10,000 GW of renewable energy capacity would need to be dedicated exclusively to green hydrogen production by 2050, if forecast increases in demand for the fuel come true.

At the end of 2020, global installed capacity of renewable energy was just 2,799 GW. Of that only a tiny fraction is available for hydrogen production, with the majority being fed into local power grids. The 260 GW of capacity added last year was a record amount, but a drop in the ocean of the gap that needs to be closed to generate hydrogen at scale.

The point of these massive numbers is very practical. If hydrogen is to become a fuel of the future, solar panels, wind farms and other sources of renewable electricity will have to be installed in sizes that dwarf anything in existence today. Imagine tracts of remote land filled with mega installations of solar panels or wind turbines, stretching as far as the eye can see.

There are places this could happen. Australia’s interior is one option. Chile’s Atacama desert has been talked of as another. The Sahara, with among the lowest population densities on earth, intense sunshine, and proximity to one of the major energy consumption areas of the world in north-west Europe, is a tantalising third. But there are significant barriers too.

Critics might say we have been here before, in the early days of European empires, conceiving of land as ‘empty’ and putting it to ‘productive’ use with little regard for the impact on existing cultures and ecosystems. Investors, meanwhile, will view Chile, Australia and Sahara very differently when they come to consider committing hundreds of billions of dollars to investments.

Why Japan and Australia work

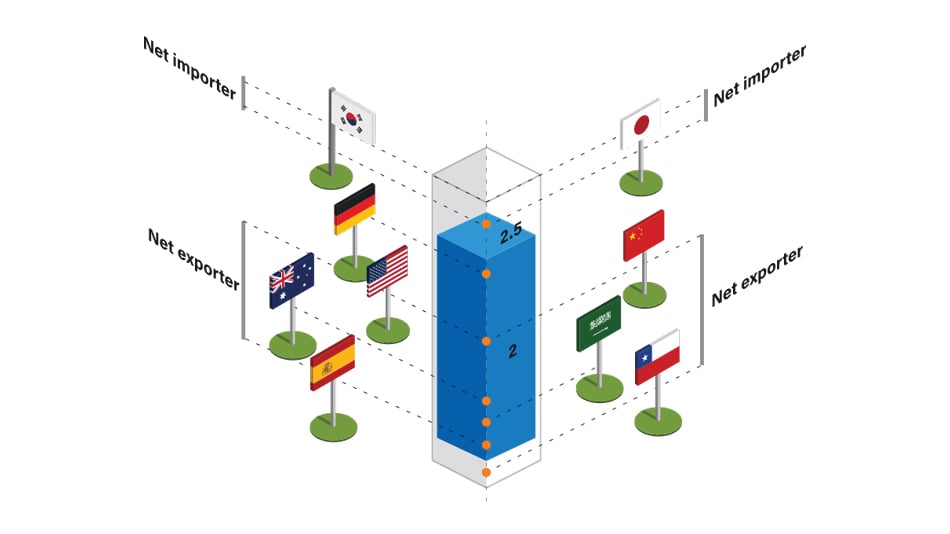

The complexity of the challenge involved is likely to require states to be involved in the solution. And that is where Japan and Australia come in as early movers, and where the governments can tell us a lot about how giant hydrogen projects may develop.

Australia has the land, climate and a need to diversify exports away from fossil fuels such as coal and gas. It is a country used to developing mega-projects with some of the world’s largest mines, natural gas export terminals and infrastructure to move materials across inhospitable land at scale. Such projects bequeathe technical know-how and banking expertise.

Japan ranks as the world’s third largest economy, with limited domestic energy sources and a history of importing fuels at scale. Its prosperity depends on industrial production, but that faces an existential threat from zero emissions policies. Unless Japan decarbonises, its industrial base faces the prospect of stranded assets, able to produce output, but unable to sell it to a market increasingly concerned about emissions.

Post Fukushima the government has settled on hydrogen assets as a major source of clean energy, and looked to Australia as the place to source it from. This will not be a one way street. Japan will expect to cushion its balance of payments with Australia, likely exporting some of the fruits of its hydrogen revolution, public transport fleets, for example.

But the key point is a country, Japan, which will be among the most expensive in the world to land hydrogen, has decided to bet on the fuel. In doing so it has turned, in Australia, not to the cheapest source of hydrogen, but perhaps the most strategically reliable for it from Tokyo’s perspective.

What to expect elsewhere

Similar strategic considerations are at work in Europe. In pure resources terms, the Sahara desert is an obvious place to produce green hydrogen. But it is not likely to be the first major source of the fuel.

Rather Germany has signed a hydrogen understanding with Australia, envisaging shipping liquefied hydrogen halfway around the world at great cost, even though waterborne trade in the fuel remains at a prototype stage.

Germany will also look to European partners. The Dutch port of Rotterdam is part of the feasibility study for shipping hydrogen from Australia. Spain and Portugal have both committed more than US$8bn to hydrogen, according to the Hydrogen Council. They may not have as much sunshine or space as the Sahara, but can commit capital to infrastructure to move the gas north.

Globally, Chile is grabbing more attention than Mongolia’s vast Gobi desert, which should be an obvious source of renewables projects to generate hydrogen for Japan. Chile has one of Latin America’s most stable economies and a track record of mega export projects, including the world’s largest copper mine, which is responsible for 5% of global production.

Such considerations can appear limiting, especially when they downplay potential hydrogen production in less wealthy states. But there is a more hopeful interpretation. The fact that governments are thinking strategically shows the level of commitment to hydrogen as a fuel, which will eventually embrace more potential sources.

For now, though, the lesson is clear. The future of hydrogen needs to be understood not only in terms of sources of supply and demand and their proximity to each other, but also in terms of geopolitics and financial markets. Production and consumption are likely to increase first where governments, large corporations and banks can come together and agree to develop projects at a scale that has been until now almost unimaginable.

This article was first published by Economist Impact and reproduced with permission.

;

;