Around the world rail service levels vary enormously. Why does such a discrepancy exist and what can we do about it? Can technology provide a solution to chronic rail sector issues?

-

John Fagan, Director, Arup London

-

Oliver Bratton, Operations Director European Business, MTR Corporation Ltd

-

Timothy Keller, Director of Rail/Transit Operation, Integrated Strategic Resources, LLC

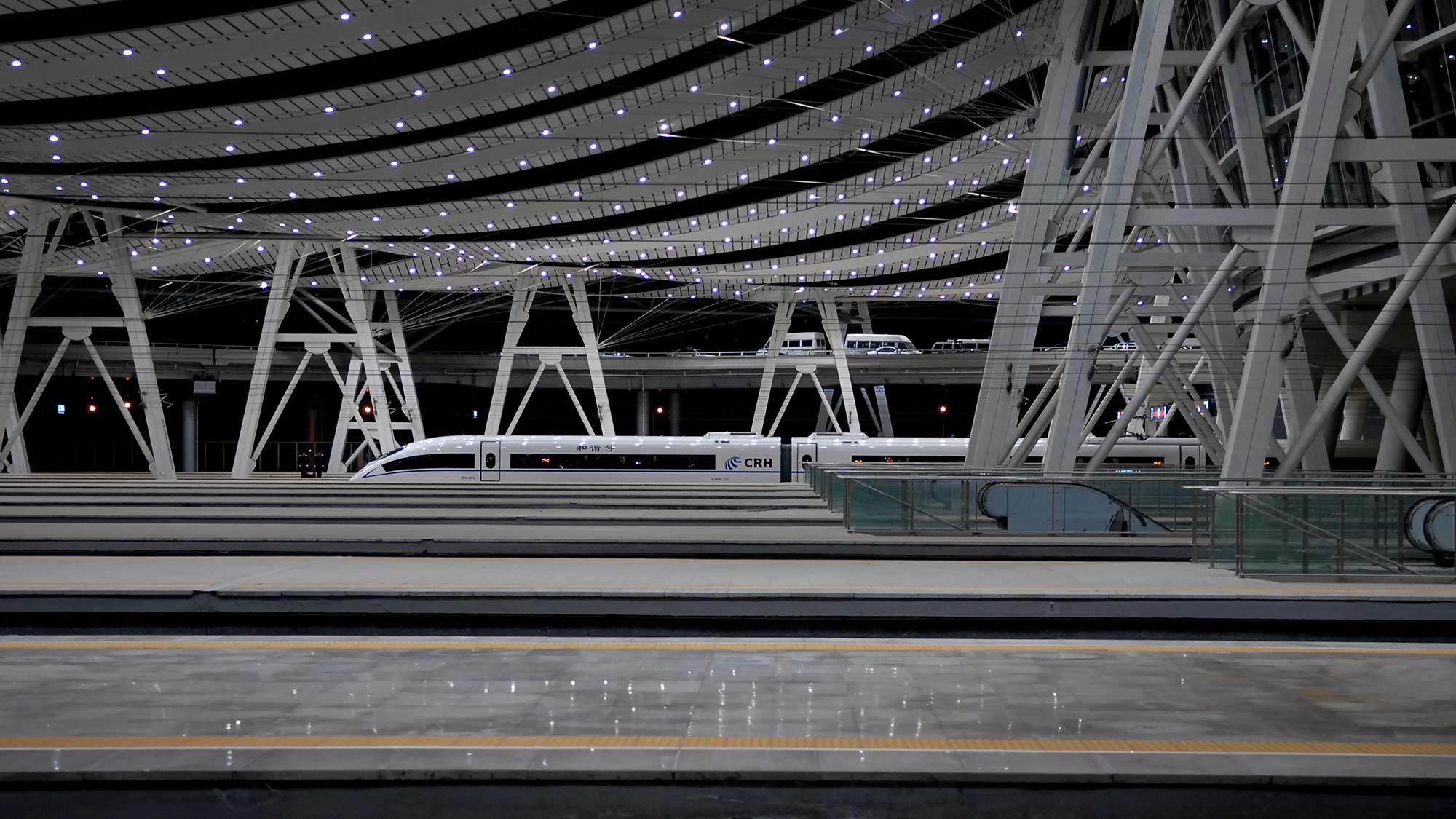

The Japanese rail system is next to-perfect and its praises are sung all over the world. Why not just replicate their system elsewhere?

OB: Organisations with extremely high levels of reliability place equally high value on reputation and brand, and won’t let incidents happen. They heavily invest in reliability and customer satisfaction but that’s not the case everywhere. For example, in Hong Kong door reliability is exceptional because every door fault is managed with an investigation followed by a detailed plan on how to stop the same problem happening again. In the UK, investment is less focused on problem-solving, despite a similar maintenance regime. This makes the UK system more vulnerable to future failures.

JF: I agree that the value of brand and reputation is important, and helps to create greater accountability. The geographical differences may be because in the UK, even on a single route, multiple organisations are responsible for overall performance. In places like Japan, while Japanese Railways Group consists of multiple regional rail companies, these companies manage all aspects of their allocated routes. It’s challenging to create ownership of reliability issues in the UK, with different stakeholders pointing the finger rather than taking responsibility. But I also agree about investment. The Japanese are spending and focusing more on resilience.

TK: Here in America, if you run 90-92% on time, everybody is okay with that. You don’t want consistent delays, but perfection is not really something that’s achievable with the current level of investment. We are investing heavily in new infrastructure, but the effects of this will only become visible in around 10 years, when it’s complete and there is a history of operation. However, investment is the key. We live on very thin margins here – far too thin to increase our on-time performance to anywhere near Japanese standards.

OB: Also, in Japan and Hong Kong property development helps to fund the operations, increasing available investment. Moreover, the Japanese railway tends to operate on single routes, which helps to avoid complex junctions and facilitates scheduling. Here in the UK everybody tries to use the same congested infrastructure, which creates a high level of complexity.

JF: Yes, to maximise capacity timetabling has become very complex in the UK as we squeeze more from the network. Our franchising process has nudged us in this direction by incentivising growth in passenger numbers. This has been delivered incrementally by running more and more services on congested parts of the network, making operational delivery challenging. There would be a real benefit in stepping back to consider how we can simplify timetables and strive for more standardisation. This would help us innovate and implement digital signalling technology more effectively, enabling trains to reliably run closer together, which would create more capacity for customers.

On the technology note, will it really be the solution to everything?

TK: Here in New York City, technology is actually a significant problem. Every time we attempt to advance technologically, the complexity from an equipment perspective increases and it seems to slow us down. Suddenly, you rely on third parties for repairs, often at the software side. But then again, technology is only part of this. In truth, you could move the trains on time if there were no people. Once you put people into the system you begin to have incremental delay. You may think that by running fewer trains over a similar infrastructure, you could achieve a greater on-time performance; on the contrary, we’re finding that if we onboard too many people to too few trains we run less efficiently.

OB: I completely agree. It happened a few years ago in Hong Kong, where they improved the performance of the system by running more trains, which, as you say, may seem counterintuitive.

In the UK, there are so many other factors to consider, such as infrastructure reliability. We are still struggling to identify what the key problems that impair service reliability are. In terms of the data and technology, expectations are moving faster than reality. It is challenging to get new trains into service because of the technology on board. This said, when we do get real-time data and technology outputs, there will be lots of fantastic things we can do to improve the customer experience and our own processes. Think of maintenance or space planning. The challenge will be to keep pace with the arising business opportunities.

TK: We face similar issues due to technology adoption, such as early obsolescence. Just when we roll out the technology, it becomes unsupportable. We have equipment that we expect to use for 25-35 years; instead, after ten years many components are obsolete, after 20 the parts are almost unobtainable. That’s something that we’re wrestling with.

I wonder if we should question the time span of our designs? Should we design for a 15-year lifespan, rather than for a 50-year span?

OB: The problem is that if you’re going to roll out a national signalling system, it will take 35-40 years. It takes time to roll out a major piece of national infrastructure across the whole country.

JF: Indeed. The scale of the investments required to develop these technologies and roll them out on a national scale means that they need to be considered over a long term if they are to represent value for money. Making the business case for investments such as digital railway and European Train Control System signalling has been challenging in the UK. The end state is attractive; however, the scale of costs and limited benefits in the early stages mean that a longer-term strategic view is essential to getting things moving.

How can we improve this situation?

JF: The industry needs people who can lead and deliver change and an industry-wide strategy that recognises the long-term benefits of technology improvements. This will enable leaders to work together to make the case for change more effectively and then implement it. Potentially, we will have to involve third parties for financing and funding and allow them to drive some of the quality into delivery. This will help us be more focused in terms of hitting timescales and getting things done.

OB: One of the real challenges is balancing risk and innovation. In 2008, we introduced new rolling stock that was built on old operating systems. This choice minimised the bugs, but it meant it was prone to obsolescence. In the rail sector, we are building on software platforms that we are managing risk on. We want it old enough that we know the bugs, but new enough that it is manageable and not obsolete: it is a really difficult balance.

Do you think this issue is being managed better in aviation?

OB: I think so, but when you buy an airliner, you are spending much higher lump sums up front. That’s not to say software systems on planes don’t go wrong, as we know. The aviation industry is slightly more mature in this market than we are.

It is evident there are multiple challenges ahead. Do you think these will impact the perception of rail? Will you need to give up some market share to autonomous vehicles (AVs)?

JF: Global trends, such as urbanisation, will place added stress on already straining systems and infrastructure.

But denser urban areas provide opportunities for rail because it relies on density to function efficiently. When it comes to AVs, my feeling is that there is an opportunity and need for integration, so that AVs provide quick, easy and comfortable access to rail services.

OB: I’m not sure that AVs can compete in densely populated areas: like cars they take up more physical space than a train. You would end up with gridlocked AVs instead of gridlocked cars.

On the note of global trends, let’s talk climate change. How will unpredictable weather challenge our railways?

OB: I don’t think there’s a simple relationship between weather and how we run train services. The challenge is that our risk appetite is dropping. We cannot control third-party trees falling on to the railway system. It partly comes down to the technology question: can we use technology better to help manage risk?

JF: In the UK we will continue to have challenges with managing weather events, because of ageing infrastructure. Using technology more effectively to model the impact of weather offers the opportunity to provide better information so that we can plan how we manage the environment around our railway.

Despite the challenges ahead, do you think that the future for rail is bright?

TK: I see the future as very bright. There are enormous opportunities so long as we provide the quick and efficient service people want.

JF: Yes, I agree. The scale of success is dependent on the pace at which the railway can evolve and become truly customer-facing. But even without that, mass rapid transit’s going to be an important feature for our urbanising society.

OB: I agree, provided we can remain competitive.

JF: Maybe these challenges are the type of wake-up call we need to push us towards more innovative approaches.

;

;