As evidence from Boston is showing us that ride-sharing services such as Uber and Lyft are increasing traffic in that city by replacing transit and walk trips, even in the transit-rich city centre, it is timely to reflect on how transport planning needs to facilitate better urban outcomes from technological advancements.

The future is always hurrying towards us. Andrew Gordon’s Book, The Rules of the Game, explores a familiar story: the technological disruption confronting the world’s navies in the late 19th/early 20th centuries as they adapted to the advent of coal-fired propulsion and wireless communications, rendering their existing methods of communication and coordination obsolete.

The author describes the British navy’s First Sea Lord’s modus operandi as "the building of castles in the air” and the role of his staff as “the rearing up of earthly foundations to meet them", meaning that instead of undertaking analysis of how to use the new technologies available, they were ex post-facto constructing the justifications for the adoption of innovations.

The Battle of Jutland in 1916 put this approach to test, and the navy’s failure to adapt their fleet management methods to future technology saw the British fleet suffer devastating losses.

Fast forward to today and coal-fired propulsion is out and autonomous vehicles are on the horizon. Well, in many ways they are already here, but fully-autonomous vehicles could be right around the corner. They have the potential to completely reshape our cities and their transport systems; in fact that potential seems to be autonomous vehicles’ main selling point.

Political figures are already calling for planners to rethink investment in public transport infrastructure in Australia and New Zealand on the assumption that autonomous vehicles will solve many of our cities’ transport problems.

“The phrase ‘transport planning’ implies we are at the front edge of things, helping to guide and direct our future transport networks and services. But too often, we have been led by the technological imperative of new developments. ”

Brian Smith

Instead of giving directions from the front, we have hurried along behind these developments, backfilling justifications and facilitating the adoption of the new (rearing up those earthly foundations), unable to catch up and with insufficient time to think about the wider consequences of new transport technologies and proposals.

At present, I see this rush to facilitate and embrace autonomous vehicles as having the same characteristics. There’s a real risk we will reverse what gains we have made in making our cities more liveable, by not creating the planning policies, strategies, frameworks and mechanisms to ensure we can reap the social and transport benefits autonomous vehicles offer, while minimising the negative outcomes.

Closer to home, the demise of Sydney’s tram network provides a cautionary tale. From 1861’s first horse-drawn trams, the network grew to be the world’s biggest. However, after the second world war, the rapid rise of the private car and the bus sounded the death knell of the tram. In 1946/7 around 13% of trips were made by car. By 1960, a year before the Sydney tram network was finally dismantled, 50% of trips were by car and by 1971, car had captured 70% of trips.

Transport planners helped to remove the trams. The flexibility of private cars and buses was seen as their great advantage over inflexible trams. Cars permitted people to live where they wanted and let industry shift away from the inner city, resulting in the sprawl and congestion many of us spend our careers trying to overcome.

Transport planning was dragged along behind the new technology of the mass-produced private car and the bus, urgently changing our city to facilitate the car.

So what are some of the risks of autonomous vehicles to our cities and why should we be concerned about them?

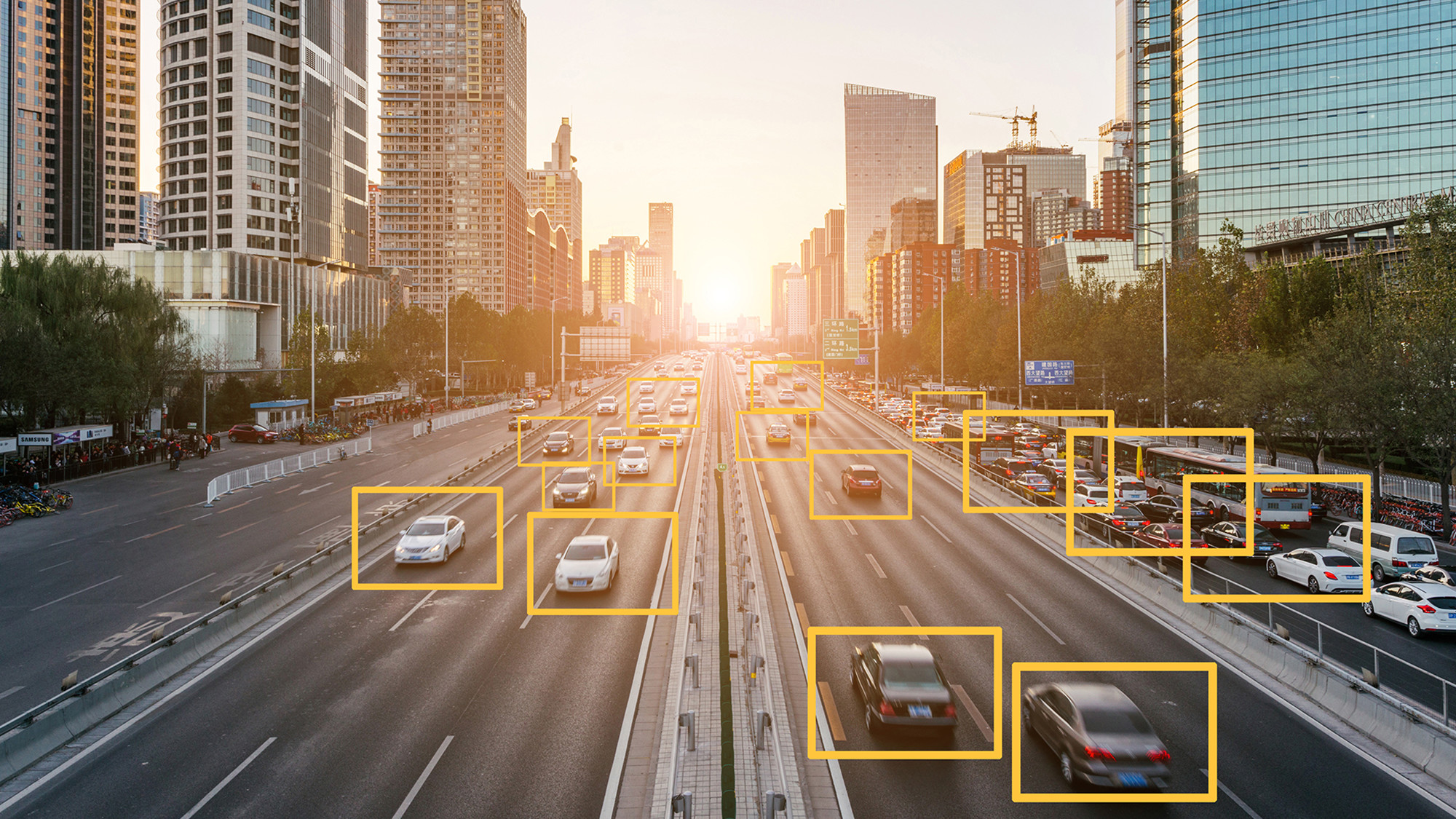

The most urgent, in my view, is the way autonomous vehicles are assumed to interact with pedestrians and cyclists (the original autonomous vehicles). Many of the benefits to the performance of the road network that autonomous vehicles can offer, as demonstrated by traffic models – increased capacity by means of closer headways, doing away with traffic lights by having autonomous vehicles navigate intersections like networked schools of fish – assume that pedestrians and cyclists are not present. As soon as they are introduced to the model, things turn to custard. The technology that helps the vehicles avoid crashes will grind things to a halt once unpredictable pedestrians and cyclists are detected.

There’s two ways for the transport planning industry to resolve this. One is to say that in busy pedestrian and cyclist areas such as cities, autonomous vehicles are excluded (after all, if we can trust the collision avoidance technology, what will stop us from stepping off the kerb at any place, confident the autonomous vehicles will stop for us?). The other way is to separate the pedestrians and cyclists from the vehicles. We already have the model for this in underpasses, overhead bridges and footpath fencing. Which future do we want for our cities?

If we look to the car manufacturers, we can get some hints about which way things are heading.

Manufacturers are taking two approaches. The first is a steady introduction of autonomous vehicle technology to new car models – automatic parking, lane-keeping technology, crash risk detection etc. All things to ease the burden on the driver and improve the safety of owners.

The second approach is to promote the urban planning benefits of autonomous vehicle technology, for instance by showing how autonomous parking technology can reduce the size of car parks (the car can drop you off then park itself in a stacked space, or a narrower parking space because the doors don’t need to be opened), making more land available for parks and buildings.

Both models aim to protect the private ownership model for cars in cities. In this version of the autonomous vehicles future, driverless cars are circulating the streets, picking up and dropping off their owners and disappearing out of sight.

A KPMG study estimated that in the USA, autonomous vehicles could unlock 1 trillion more miles of driving by 2050, partly by providing mobility to the old and young who may not be travelling now. In accordance with the principles of induced demand, the space autonomous vehicles make available will immediately be filled by more travel demand.

In Sydney, almost 80% of CBD workers use public transport to get to work. If only a few percent of these workers shift to an autonomous car, how could we accommodate them on our streets?

I suspect most transport planners would prefer to see fewer cars in our cities, rather than more. We want to see our cities made even more pedestrian and cycle friendly. There are good social and economic reasons to do this. So how do we harness the potential of autonomous vehicles to achieve this outcome?

As transport planners, we have a clear choice right in front of us. Do we follow behind as the technology determines the outcome, or do we grab opportunity by the forelock and shape the autonomous vehicle future through policies, strategies and planning frameworks to deliver better cities and a more sustainable and safe transport network?

Find out more our work with autonomous vehicles

;

;