I think active transport infrastructure holds the key to solving the housing crisis.

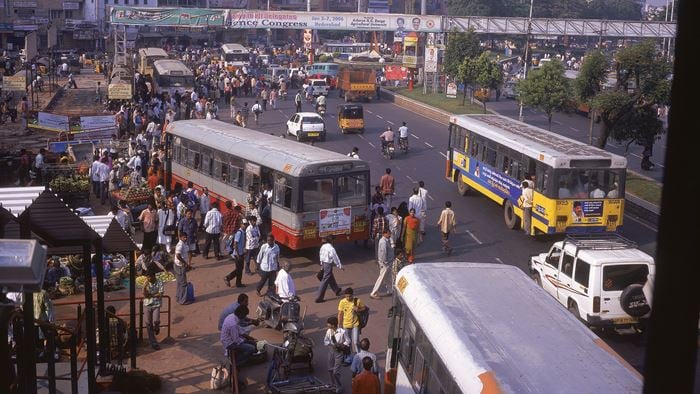

Many major world cities are suffering from a chronic shortage of housing. The solution isn’t as simple as just building more homes. All the city’s residents have to be able to get around the city too.

That’s why housing density in London (and Toronto, Manchester, Cardiff and Abu Dhabi among others) is linked to public transport provision. If there aren’t the rail, bus and tram services to keep new residents moving, high density housing would lead to unacceptable rises in car use, with associated congestion and pollution. Hence planning laws are often used to restrict the area’s housing density.

But public transport accessibility formulae (such as the PTAL system in London) take little or no account of active transport infrastructure like cycle paths and walking routes.

If there were better active transport infrastructure, more of it, and more people using it, then more homes could be accommodated. In this way, I believe we could potentially double the permissible housing density across half of Greater London, for example. This is the idea I submitted to the New Ideas for Housing International Ideas Competition run by New London Architecture and supported by the Greater London Authority, and I’m pleased to say it’s been selected as one of the ten winning entries.

So what would this look like? For people on bikes, we need more segregated cycle paths so that riders feel safe even when the roads are busy. Pedestrians want to feel that they’re safe from vehicles too, and protected from street crime. That means wide pavements and well-lit streets. And people both walking and cycling need routes that are direct and convenient, with good signage.

The benefits don’t just include more housing. City residents would be fitter and healthier. In a world with growing epidemics of obesity and inactivity, this would reduce strain on health services. It’s less polluting, with no harmful nitrogen dioxide or particulate emissions, and virtually no carbon dioxide.

It’s cost-effective, too. In London, for example, the Mayor and Transport for London are currently constructing 15km of segregated cycle lanes for a cost of £59 million. That’s substantially cheaper than the £1bn it’s costing to extend the London Underground 3km to Battersea.

That’s not all: walkers and cyclists spend more money locally, so you get a thriving local economy and a stronger sense of community.

What will it take to make this a reality? Well, I think both city leaders and the general public will need to change their mindset. We need city leaders to see active transport as a solution rather than just an afterthought.

It’s been said that cycling infrastructure in particular only benefits young, healthy men – that women, children, older people and those with mobility problems can’t or don’t want to walk or cycle. I don’t buy into that argument. If we had the kind of high-quality active transport infrastructure you can see in Copenhagen, for example, it would be attractive to many more people.

We need to change the perception of cycling so it’s seen as normal, and accessible to everyone. That’s exactly the situation in the Netherlands, which has the best cycling infrastructure (and the lowest obesity rate) in the western world.

If we’re agreed that our cities are going to grow, and that we need to build more homes, then active transport infrastructure would not only make this possible, it would make our cities better places to live for everyone.

;

;