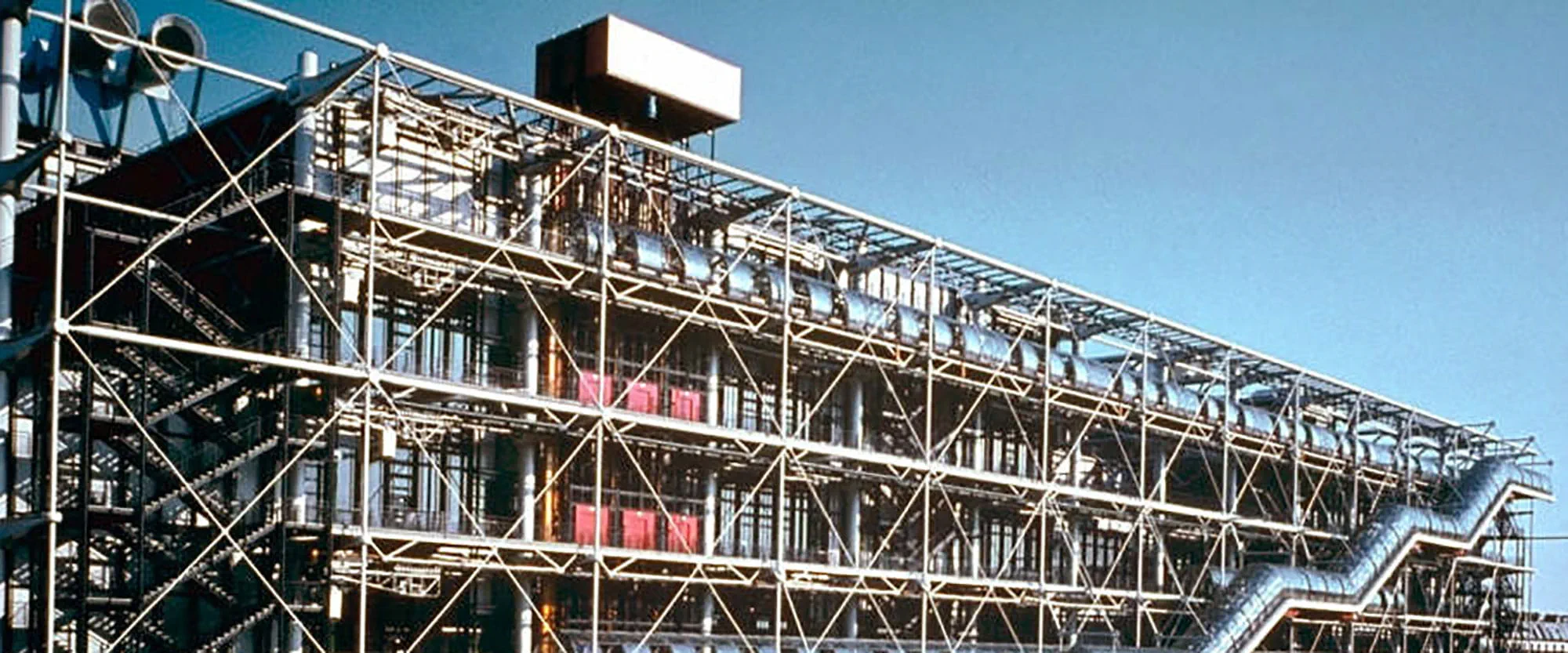

Technology may have moved on since the 1970s, but there’s still a lot we can learn from the focused and bold approach to building the Centre Pompidou in Paris.

Frankly, I think today in Europe we’d struggle to match the timescale in which the project was designed and built. The design competition was held in June 1971 and the centre opened in the first few days of 1977. For an incredibly complex and innovative building, this is an amazingly short timescale.

So how was it done? It started with the French government taking a risk on architects who were then young and unknown: Renzo Piano and Richard Rogers. Piano was 34 when he won the Centre Pompidou competition and he was still in his 30s when the building was completed.

I don’t think a national government would put its faith in such a young team today. In fact, in our checklist-driven, bureaucratic world, I doubt they’d even make it through pre-qualification. With the industry now much more risk-averse than in those days – particularly public sector clients – many inspirational projects probably fall unnoticed at this first hurdle.

As it was, the young, hard-working design team, which included Arup’s Peter Rice, came together in Paris and worked together in an office near the site. This hothouse environment enabled them to push the design on quickly. For large international projects today, teams can be spread around the world. Inevitably, communication is not as slick.

I think there’s also a tendency to over-analyse, spending too long trying to get the last 1% of structural efficiency. In a previous post on Thoughts, Martin Manning asked if we designed better buildings before we had computers. I’d say that we often use the computing tools we have today to prevaricate rather than make decisions.

Computers don’t necessarily lead to efficiencies but had we used today’s tools on the Centre Pompidou, we might have gained some marginal improvement. We might have been able to design the same building with 10% less steel or 10% less mechanical equipment, for example.

The real difference between then and now is the context in which we’re working. One of the most innovative elements of the Centre Pompidou – using water-filled structural steel columns to provide fire protection – was born out of necessity. At that time, the French authorities insisted on a code-compliant design. Today they’d be open to less complex solutions if calculations showed they were safe.

However, authorities today would also require the building to be much more energy-efficient. Placing building services on the outside gives the Centre Pompidou its iconic ‘inside out’ form and opens up space inside but it also creates a vast number of cold bridges where heat can get out.

There’s also another reason why we’d think long and hard about putting all the mechanical and electrical systems on the outside of a building today: it is much harder to keep them in good condition when they’re exposed to the elements. In any case, the architectural agenda has also moved on.

The legibility of the Centre Pompidou – the way you can read the building’s engineering in its architecture – or similarly the Lloyd’s of London building is not repeated in today’s iconic projects.

For some engineers, the Centre Pompidou and Lloyd’s of London were the golden age – when engineering design was central to building form and their work was on show to the world. But times change and today there is a new set of agendas to understand, for example in the way buildings can aid social interaction.

As engineers, it’s down to us to understand and respond to these agendas just as creatively, effectively and innovatively as the people who designed the Centre Pompidou did to the challenge they set themselves.

;

;