From December 2018 through March 2019 the Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum in New York City is hosting The Road Ahead: Reimagining Mobility. The exhibit presents 40 design projects inspired by the technologies that will change how we move people, goods, and services in the future and encourages visitors to consider how those technologies can make streetscapes safer, transportation more equitable, and cities more sustainable.

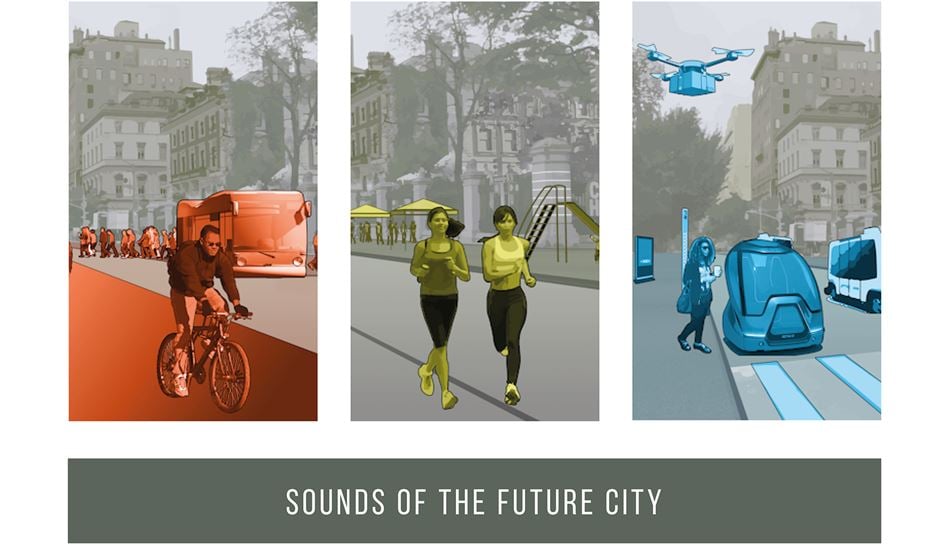

As part of the exhibit, Arup created Sounds of the Future City, an immersive 3-D sound experience with three scenarios that invite visitors to imagine how cities might sound in the future as new technologies arrive in public spaces. Here, four of the key collaborators, Rachel Abrams, Chris Pollock, Léonard Roussel, and Raj Patel discuss the inspiration and creative process for this experience, as well as the power and impact of prototyping in design.

*

Q: There has been a lot of positive response to Arup’s installation in the Cooper Hewitt’s exhibit The Road Ahead: Reimagining Mobility. Where did the journey start?

Raj: The idea started out simply: to use sound to help people better understand their experience of the city now, and then posit what a potential future experience would be like. But that’s a very lofty goal, and very high-level, so we had to go through a process of determining how we would convey that story to the public. It was a design question first — what are the influencing design factors that play a part here, and how do you bring those together?

Chris: It was important to us that we embrace the overall message of the exhibit, both so our piece had context and so that we could reinforce that work on the part of Cooper Hewitt of posing some important design questions. From there, as Raj said, we started to ask ourselves: What do we want people to experience? What are we trying to have them think about and feel? What are we trying to provoke them to think about, and how far should we stretch the ideas?

Raj: Absolutely — a very important part of this piece is to show the opportunities and the challenges for what the future could be like in a balanced way and instigate some critical thinking in people when they experience those potential futures.

Léo: In that way, the setting for our experience was important. Early in the creative process, we decided to use a real location, where we could extend the experience out to the street after people leave the exhibit, so that they could experience the intersection in real life and really feel the weight of the questions we were posing.

Q: So what happens next — once you have the idea, how do you move that into reality?

Rachel: From the initial context to the actual design process, there were several constraints on this experience. One was the fact that we are simultaneously the introduction and the conclusion of the gallery experience, which, as Léo mentioned, was one of the main reasons we based the experience on the street right outside the museum. Another was focusing our knowledge and our thoughts around this vast future-facing topic to be accessible and relevant to a wide audience.

We needed to use our expertise to not necessarily arrive at answers but rather to set out propositions — and we needed to do it in a way that is simple enough to be engaging to an eight-year-old encountering these questions for the first time and compelling enough to other experts from the design community.

Raj: It’s a challenging balance. A lot of people talk about human-centric design today, but I'm not sure that they really understand or know what human-centric, or rather people-centric, design is. It’s about the whole experience, about the process as well as the outcome.

I often challenge architects and designers that I'm working with — instead of asking what a project is about, I ask, “How do you want people to feel?” To get insight into user experience and to do real people-centric design, you have to design for the senses. To understand sensory design requires virtual and real prototyping to be effective. Sound is integral to high-quality design experiences. Our tools bring this to life in the design process across a wide range of industries that are essential to the built environment.

Chris: This was a very collaborative process as well. The planning team developed those three scenarios, along with Rachel, who provided the narrative. Then we had to form a baseline: What does the city sound like today? How do we quantify that? How do we measure it, and use it, and record it as an asset we can use to create this realistic 3-D audio, this spatial-audio experience? From there, Léo and the team went out to do a series of captured recordings and observations to start that process to create a believable, immersive city soundscape.

Léo: Because the intent of the piece is to pose relatable and persuasive questions to the audience, we need to trigger an emotional response using memory, which is a complex network of past experiences. So we created a realistic scene that obeyed the general rules and paradigms that street soundscapes are built upon — mainly that street soundscapes are layered on top of each other and have specific properties that can be described in terms of depth of field, granularity/singularity, trajectories, and content stationarity/variability. Playing with these four dimensions at once is a unique ability made possible by 3-D audio.

All of this was storyboarded very carefully. We wanted to make sure that the emotional connection and the responses that people were having were instigated by sound. The visual component of this experience is almost exclusively informative — it provides grounding context for the audio experiences and poses the framing questions that introduce the wider theme of the exhibit. But it’s not as simple as just re-creating the existing audio of the street outside. If you are creating an audio experience to create a certain response in an audience or to posit important questions through that experience, you must be careful to build as close a reality as you can without overwhelming people.

Depth of field: Sound-emitting elements are distributed on a spectrum of distances from close foreground to deep background.

Granularity/singularity: Sound layers have different spatial distributions that are unable to be separated into individual source components, from sounds in the foreground to ambiance in the background.

Trajectories: Sources of sound can move in space. Background layers are usually perceived as still, but the motion of middle-ground and foreground components is perceivable.

Content variability/consistency: Audio content can be stationary or vary greatly in time — for example, a car can move through space, but its sound texture does not vary in time.

Raj: Yes, exactly. You can't make a full, realistic city because there’s too much going on. In a live situation where you’re on the street, your brain interprets all that audio stimulation and makes sense of it. If you hear the sounds of the street at the same level in an installation as you heard them outside, your brain won’t be able to process it, because you're inside and cognitively you don't expect that same level of audio stimulation.

Rachel: As a design artifact — if we imagine that we have been commissioned to think about this for a city or a vehicle manufacturer, as a piece of prototyping — it’s about always trying to strike exactly where it’s high fidelity enough to where you've got just enough information in there to be plausible and that considers the constraints that the client is thinking about.

Q: What are the major benefits of this type of prototyping? What insights can we learn?

Rachel: The design enterprise is mostly about shifting from the what is to the what could be. Prototyping is essential to this speculative practice in all sorts of ways, moving designers from the potential to the actual.

At the heart of the process, iterative prototyping is a way to test a concept, learn from materials, or solicit responses from target users to refine and commit to the form of a concept. Physical and screen-based prototypes also provide feedback, allowing designers to learn by doing, as they interrogate and focus on specific aspects of a deliverable. Even brief, simple prototyping with video and audio, like the scenarios we’re showing to Cooper Hewitt’s visitors here, can inform and enrich Arup’s projects, from interventions in a single street or at scale for a whole city.

The power of prototyping is that it allows designers to rehearse ideas before committing to them at one-to-one scale, as well as communicate complex ideas and convey experiential outcomes to clients and collaborators.

Sounds of the Future City was designed by Arup consultants and specialists Rachel Abrams, Willem Boning, Terence Caulkins, James Conway, Anthony Cortez, Casey Eckersley, James Francisco, Kelsey Habla, Sean O'Neill, Raj Patel, Chris Pollock, and Léonard Roussel.

;

;