Starchitects aside, we hear little about the individuals whose cumulative decisions shape the built environment. At Arup, the quality of our work has always been inextricably linked to the quality of our people. As we strive to meet society’s coming challenges, we pause a moment to learn a bit more about those individuals who have shaped the past, are building the present, and imagining the future of the built environment.

Alisdair McGregor, a principal and Arup Fellow in our San Francisco office, spoke with Arup’s Kelsey Eichhorn about energy, innovation, and musical duets.

How do you describe what you do to people who aren't in this industry?

The short answer is I'm trying to design buildings or neighborhoods that use as few resources as possible, but still produce a great place to live, a great place to work.

And I actually started on that path fairly early. I think the educational system in the UK makes us specialize far too soon, but it worked out OK for me because I enjoyed building things. My undergrad degree was in civil engineering. I worked for a contractor for almost three years, then went back to university to do a research doctorate. That's really when I got interested in energy in buildings. After leaving Leeds University I was looking for a design firm that was multidisciplinary, and that is what attracted me to Arup.

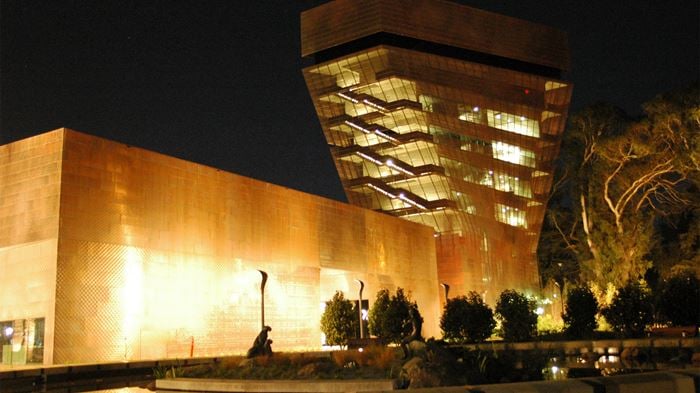

Lloyd's of London

Did you work in the London office when you started?

Yes. The first project I worked on was the Lloyd’s of London building, which was a pretty radical design at the time. All the engineering services were exposed, so there was a lot of coordination with the architects, Richard Rogers Partnership.

That's where I really got the bug for doing what I do, working with the whole design team to produce the best building — not just the best mechanical system. I was also fortunate to have the late Peter Rice as our group director and the structural leader of the Lloyd’s project. His intellect and creativity were an inspiration to me.

You said your doctorate focused on energy in buildings. Was that something a lot of people were focusing on at that time?

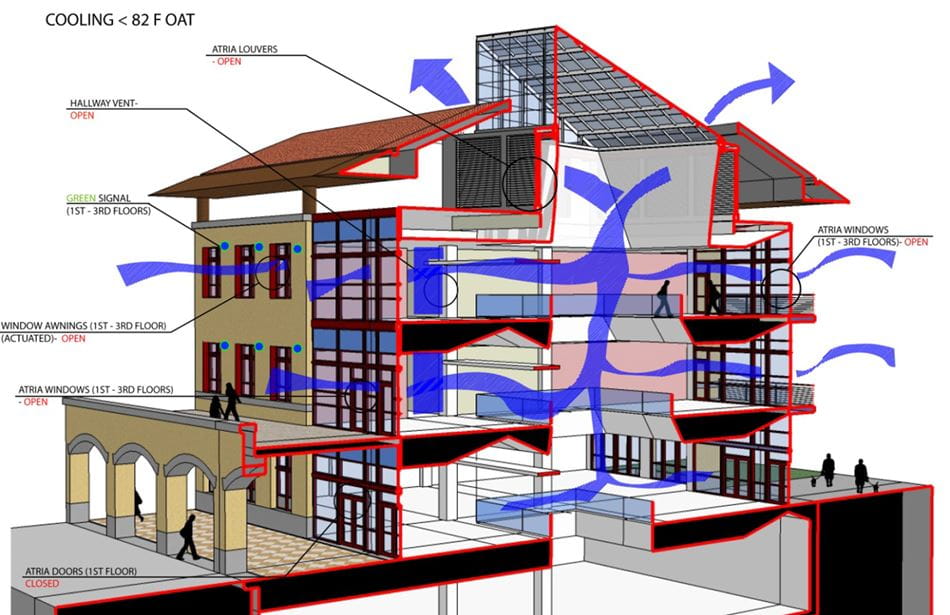

Not so much. Traditionally you would design the mechanical systems only after the architectural design is done, whereas my PhD work looked at energy flows through buildings — basically thinking about how you would design the whole building to make it work better from an energy standpoint rather than leaving the engineering to the end. Now on all our projects we try to see how far you can design the building without the mechanical systems — thinking about building massing and passive systems, for example. When you've got the building performing right, then you start looking at, "What mechanical equipment do we need to put in?"

How was that transition from working for a contractor to academia and then back to working for a company?

There were a number of things that led me to going back to doing research. When I was working with the contractor, and for a short time doing independent design contracting part time, I was playing saxophone in a rock band. We were trying to make it. I thought if I worked part time we'd get a bit further. We had a lot of fun but never got a recording contract, so we decided to call it quits.

Almost on a whim, I applied to do PhD research. But after three years of working with academics, I decided that really wasn't where it was at. But I gained a lot from both of those experiences — the academia is what pushed me into this interdisciplinary mindset, and funnily enough what taught me to look for opportunities outside my formal education track. And I still really enjoy music. I didn’t start playing saxophone until I was 18 but actually, I recently said, "You know what? I'm going to pull out that saxophone that's been sitting unused for almost 40 years." Then my wife said, "Okay, well I'm going to start playing the piano.” So we play stuff together.

There’s a lot of talk in the industry about innovation. As someone who embraces the interdisciplinary side of our industry, what does innovation mean to you?

I struggle with the term “innovation.” A lot of what we do is not really coming up with something entirely new but combining things in a way that they haven't been combined before. It's going into an early design meeting and listening to all the different impacts and influences on a project and then working out what we can do to make it better. Is there a process in the project that we can take waste from and use that waste for something else? That kind of thing. But that doesn’t mean that innovation isn’t useful and there are certainly many challenges facing the built environment that need to be tackled from a new perspective, even if we aren’t reinventing the wheel.

What are some of those challenges?

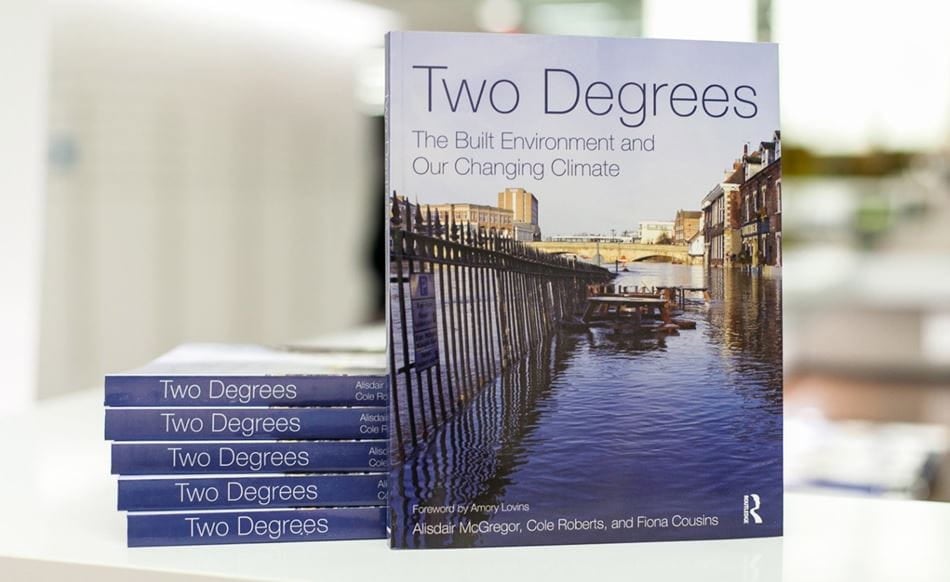

Well the biggest issue that is facing us is climate change. Countries that have signed on to the Paris agreement aren’t actually reaching their targets in terms of CO2 reduction, so the time is really running out. We have two major responsibilities as designers. One is improving the sustainability of our designs. But we can’t do that unless we can convince our clients and collaborators — whether they are public sector or private sector — of the importance of taking a long-term view. So that’s our second responsibility. At Arup we have some really great clients but to some extent everyone has to balance that pressure of short-term versus long-term interests. So climate change is absolutely an area that needs a new approach, that needs as much innovation as we can muster.

From the standpoint of climate change mitigation, what do you see as the most promising things happening today? What could actually make a big difference?

In the early 2000s we got to what I call the dilemma of the net-zero-energy building. You want a net-zero-energy building, so you go out to one of the business parks in San Ramon Valley, where I live, and build a two-story building, put PV on the roof and over parking lots — you've got a net-zero-energy building. But the carbon impact of everyone driving their cars there negates the whole benefit of doing it. Whereas if you build an energy-efficient building in the city, it's very hard to make it net zero because you haven't got enough real estate to put PVs up, but your transport impact is much reduced.

Now people are recognizing that you have to get that balance right.

That conversation probably looks very different in different places, though. So many people prefer suburban lifestyles.

I think that's changing. Not everywhere, but certainly in San Francisco. Of course, the downside is that that's driving up housing costs. It's not an easy problem to solve.

But thinking at a neighborhood or city level is something that’s fascinated me for quite some time. There are so many opportunities to create big solutions, and in our office we have technical people for all aspects of that. You can just actually have these casual conversations about how you get everything to work together.

That’s one of the things that I still enjoy. We have a lot of really smart people at Arup, and we listen to each other, talk to each other. I've never been in a position where I come in and say, because I'm a principal, “This is what we're doing. Don't argue with me. I've made my mind up." There's this constant intellectual discussion around trying to do things better. And you really start to feel the potential of the next generation. You’ve done your best to address the challenges you’ve experienced but there’s always more coming down the road, so if I was going to offer one piece of advice to the young designers out there it would be to learn your foundations well, but then keep your eyes open. Try something different and look for the opportunities to continue to learn.

;

;