Multi-storey car parks emerged as a mainstream building typology in the 1950s with the rise of mass car ownership and commuter culture. Typically constructed from in-situ concrete, with deep floor plates, low floor-to-floor heights and open facades, they are functional, if uninspiring, and often perceived as cold and uninviting spaces.

So why, in 2023, with unprecedented changes in commuting patterns, a huge uptake in active transport, and the advent of driverless vehicles, has the design of multi-storey car parks remained largely the same?

The challenge

While there have been major advances in carpark design, and the odd moment of innovation, we are still seeing the design and construction of ‘business-as-usual’ multi-level parking structures. These tend to present a range of limitations and challenges:

-

Inefficient: commuter car parks can be an inefficient use of space, with facilities reaching capacity during peak times - such as the weekday morning and evening influx/exodus - and underutilised outside these periods, such as evenings and weekends.

-

Carbon intensive: widespread use of in situ concrete carries with it a heavy carbon price tag.

-

Lacking flexibility: the structural grid and floor-to-floor heights are optimised for vehicles, and don’t typically lend themselves to alternative functions either on a weekly or longer-term basis.

-

Poor neighbours: with many car parks made of concrete and lacking a façade, they can appear to be incomplete, contributing little to the character of urban environments.

-

Uninviting and contribute to poor perception of safety: low ceilings, deep floor plates and enclosed stairs can make for dark, uninviting spaces that feel unsafe and unloved.

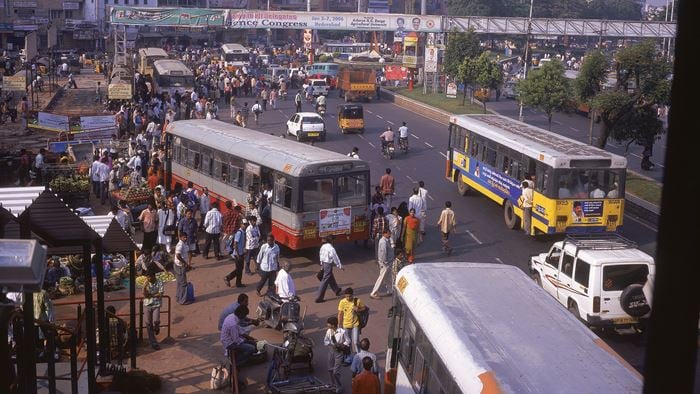

Disruptors and changing customer behaviour

Rapidly shifting behaviours in the ways we work, travel, meet, and move around our cities, leaves us with a huge array of parking assets which are fast losing relevance, value and usefulness.

Automated vehicles will radically disrupt our current behaviours and the way we own, use and park ‘cars’. In some instances, it is reasonable to assume that the need for parking in our cities will drastically decline, as self-driving cars can find alternative parking and automated vehicles can be used constantly, rather than remaining inactive for eight hours per day and overnight.

There are also increasing political ambitions for car-free cities as governments strive to achieve their net zero goals.

The fundamental issue has rarely been addressed: what happens when our parking needs change so drastically that the structures built to house parked cars are no longer economically viable? The answer is, they are demolished.

The starting point

The carpark conundrum is one that our architects have been considering for some time. The conversation gained traction in 2021 when By & Havn, Copenhagen’s city and port development company, approached us. They were tired of having to build parking houses they knew would become obsolete in 10-20 years’ time, when car access to the city would be further restricted, and the shift towards driverless cars, and public and active transport increased. Through Arup University’s Invest-in-Arup programme, we studied this trend, and explored how we might rethink the carpark typology to avoid future redundancy and waste.

The launch pad

It soon became apparent that this trend was not isolated to our clients in Scandinavia. Our team in Australia started talking to a transport agency – tasked with delivering a monumental number of parking spaces – about our research and we investigated a new approach.

Rethinking the typology

As is our approach, we assembled a multidisciplinary team of architects, urban designers and structural, services and fire engineers to explore the challenge from a range of angles. We uncovered an opportunity to bring a whole-of-life approach to a carpark project by considering the multiple iterations of a building’s life and its possible futures.

First, we challenged our own understanding of ‘what is a carpark?’ and the answer to this question is best understood when a timeframe is applied. There is need for parking cars at sites now and in the future; however, our needs will change dramatically and diversify beyond the spatial requirement to store a car. Automated vehicles, ridesharing, public transport, electric vehicles (EVs), and active transportation will contribute to a seismic shift in how we use space.

Using a circular economy approach we came up with high-level strategies on how we could deliver practical solutions for this new approach to carpark design. Not simply blue-sky concepts, but options to solve the real problems carpark owners need to solve.

Our solutions explore several different approaches to a site, whether to build the foundations of a long-term reusable form or something that can be removed for reuse in other locations.

Design for expansion and contraction

A solution offering an expandable or contractible structure can enable a carpark to respond to changing demand over a mid- to long-term time frame. A kit-of-parts approach can enable a carpark to change in scale over time through the removal or addition of structural modules. Where a structure is reduced in scale, there is scope to ‘give back’ a portion of the site to facilitate new land use or the creation of new public space.

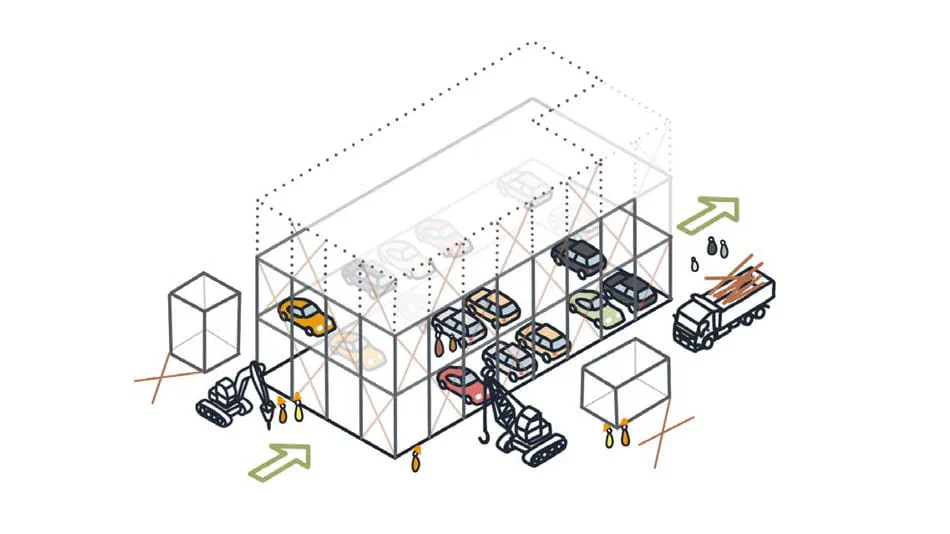

Design for disassembly

Multi-storey carpark structures are well suited to designs that allow for disassembly, transport and reassembly in a new location. This approach may suit sites where there is an expectation that increased parking demand is short term. For example, early in the lifespan of new train stations in areas where walkable residential development is planned but not yet underway. Such designs can meet short-term needs where people will drive to a station that will later serve a community that lives within walking distance.

The rational grid and simple suite of components, along with a lack of servicing requirements, means reassembly is less complex than other building typologies, even if the building geometry is altered. A kit-of-parts design is suggested to simplify and enable disassembly, transportation and reassembly, whether as another carpark or reconfigured and adapted to serve a new function more relevant in the future. Where a new function is proposed for the future, further flexibility should be embedded in the kit-of-parts design, enabling new floor-to-floor heights, block depths, façade additions and services.

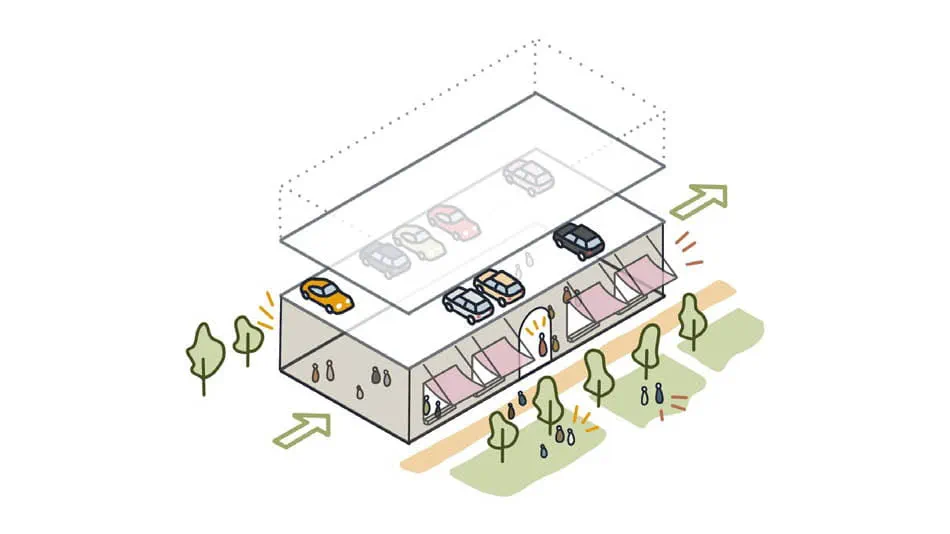

Design to enable use change

Perhaps the most attractive approach when a whole of life mindset is embraced, is we can design a carpark with embedded flexibility to enable and encourage change of use as carparking requirements change or subside over time. Day one carparking efficiency may be slightly impacted, but when considered over a building’s lifecycle a different picture is painted where the value of an asset is perpetuated through its ability to adapt.

Potential new uses beyond the carpark are wide ranging and should be considered when designing the base build. It is important to note the building requirements for alternative uses are highly varied and must be understood to ensure the building has the inherent flexibility required for the intended future use. This scenario can be an effective method to future-proof the structure and limit the need for demolition when carparking demand changes.

Beyond car parks

As we explored carpark design, it became clear that these designs offer us a simple starting point for new approaches to more complex projects of all kinds.

We cannot afford to continue to design only for the immediate need. If we are to achieve our goals in the decades ahead, we must end the cycle of build and demolish and bring true circular economy thinking into our engineering and architecture.

Together, we must embrace a fundamental rethink on how we asses need, design, construct, deliver, and repurpose our buildings to enable a continuous reimagining of their form and function. It’s time to embrace a new mindset.

Connect with Luke Smith on LinkedIn.

;

;