As planners, we should always be striving to better understand the needs of those we are planning for, because our planning and design decisions have real effects on people's lives.

As new data sources and digital innovations deliver large increases in travel information to transport planners, there is a risk that easier access to data will increase the distance between planning practice and the individuals we affect. We have a great opportunity to harness emerging data sources and digital methods to better understand the people we are planning for; but we must demand a focus on people from ourselves, our peers and our clients.

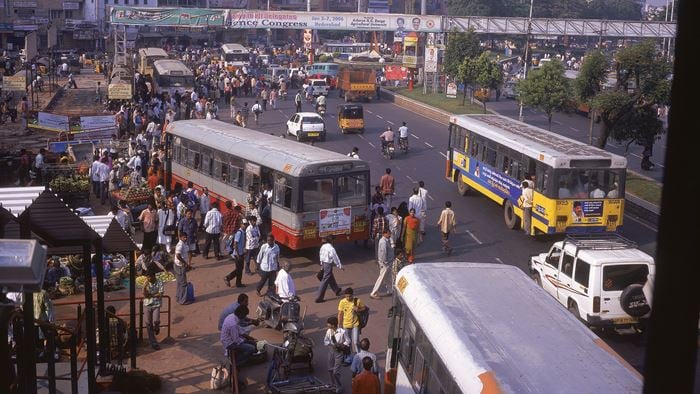

Transport planning is full of numbers – flows of vehicles and people in units per hour, patronage forecasts, measures of delay and levels of service, numerical warrants for justification of infrastructure, and simulation tools that model the movement of pedestrians, vehicles and freight.

It’s easy to forget that the planning and design decisions we make affect the real people those numbers represent – real flesh and blood people going about their lives and making rational and not so rational decisions.

“People are messy. They make decisions that sometimes seem strange and their behaviour is influenced by things we struggle to understand. Because of this, aggregating their behaviour has been necessary for a lot of transport planning work ”

Brian Smith

At the same time, transport agencies are asking us to make people the focus of our work.

The NSW Government for instance says “The customer is at the centre of everything we do in transport” and Queensland’s TransLink agency, responsible for the coordination and integration of train, bus and ferry services, operates with “a customers first focus”.

I had a vivid demonstration of the value of this customer-first approach many years ago in Rotorua, New Zealand, where I was working on restructuring bus services. At the time, Rotorua had high unemployment and some of the worst social deprivation in the country, so the bus network was intended for (and mainly used by) transport disadvantaged people. Fewer than 1% of residents used the bus to get to work. It’s also a tourist destination, so many jobs are in businesses that cater for visitors, with plenty of late-closing restaurants and supermarkets.

The Rotorua bus network had been designed consistent with best practice bus network planning at the time. Most houses were within 400m of a bus route, meaning that the bus routes meandered around the suburbs in big one-way loops and only operated every hour.

I rode the buses all around Rotorua for a week to get a feel for the network and its customers. What I saw on the buses convinced me that the way the bus network had been planned and managed was failing the people it was intended to serve.

Many bus users have few alternatives in employment and travel, so I saw people who were on the bus travelling to their jobs, making phone calls trying to arrange for people to pick them up at the end of their shift, which finished well after the buses stopped running. Many of the town’s casual employers, like supermarkets, opened ‘til 10.00pm seven days, but the buses stopped running at six on weeknights, earlier on Saturdays and didn’t run at all on Sundays.

Essentially, there was almost no match between the community’s need for travel, and the principles that were used for planning the bus services in the town.

In conventional public transport planning, the accepted wisdom is that people demand frequency and reliability most of all; but in Rotorua, the best improvement we could make would be to match the bus services’ span of hours with the actual times people who rely on them need to travel to and from work!

So, how do we make sure we really do put people at the centre of transport planning?

New developments in big data analytics and digital capabilities give us the opportunity to better understand travel behaviour at a much finer grain, including the ability to dynamically track and analyse individual travellers. However, at the same time, we can do site visits via Google Streetview, and the lag between data availability and the development of analytical tools that let us put the data in context, means there’s a risk of entrenching or increasing the distance from our customers.

As planners, we need to think beyond compliance with the usual standards and beyond transport planning generalisations, warrants and prevailing practice and make sure we dig deeper. Make identifying and understanding the customers of the transport and mobility product we are offering, a priority. We have a great opportunity to harness emerging data sources and digital methods to better understand the people we are planning for; and to ensure that people remain the focus of our work.

Thinking beyond compliance – or best practice – doesn’t mean abandoning tried and true planning principles, but requires us to remember that we are helping to shape peoples’ lives – go beyond the aggregated data and walk in peoples’ shoes.

;

;